Postgraduate medical education has been the subject of major and fundamental review. The UK’s four health ministers have set out the underlying principles of this in Modernising Medical Careers (Department of Health, 2003, 2004a ). These principles incorporate a number of trends that have emerged in medical education. Training is becoming more outcome-based, with a move away from the apprenticeship model to a more structured and systematic approach emphasising the learning and development of skills (including skills for CPD). This involves a shift from time-based training to a trainee-centred, competency-based model. Alongside this, the service commitment of doctors in training is increasingly determined by their accredited acquisition of skills and competencies. There will be a strengthening of structured training programmes that define curricula and show clear quality assurance processes wherein teaching and learning occur in a variety of settings. In sum, these changes are part of the increasing ‘professionalisation’ of teaching in medicine and will be accompanied by other changes such as the accreditation of all involved, from educational supervisors to programme directors.

For psychiatry, consideration of what constitutes ‘good clinical care’ and the working life of the consultant are fundamental to understanding the desired outcomes of training. The latter is the subject of some debate. The current position is helpfully outlined in Guidance on New Ways of Working for Psychiatrists in a Multi-disciplinary and Multi-agency Context (Department of Health, 2004b ). This publication highlights the need to develop knowledge, expertise, skills for lifelong learning (CPD), team-working (with fellow professionals, patients and carers) and a value-driven ethical basis for practice.

New training methods are being introduced within services that are themselves in a state of flux. Legislation such as the European Working Time Directive (Council of the European Union, 1993) and policy initiatives such as the National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999) and NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2000) are forcing considerable changes in the NHS.

In common with all aspects of training, specialist training will from autumn 2005 come under the auspices of a new government body, the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB). Its principles will be in line with the changes described above.

Competency-based learning

The new competency-based learning emphasises outcome in the form of performance. This is judged not simply on what a doctor does, i.e. performance of tasks, but also on how these tasks are approached and the level of professionalism shown (Reference Harden, Crosby and DavisHarden et al, 1999). There is an emphasis on teaching clinical skills that necessitates the development of patient-based approaches to learning. Many will feel that patient-based teaching is what they have always used. This may be true but as we move to systematic approaches there is a need to be more efficient and focused. Patients present according to their clinical need not to the individual’s training need. Care is required in the selection of patients for teaching. Documentation for portfolio purposes needs to be carefully considered. The attitudinal shift that is required is important. It means moving from an objective and distant biopsychosocial model towards more awareness of the impact of illness on patients and carers. There is increasing evidence that learning on simulated patients does not match real-life practice (Reference Kneebone, Scott and DarziKneebone et al, 2004). Thus, patients and carers potentially have an important role in medical education.

The fundamentals of patient-based teaching

Patient-based teaching is the teaching of clinical skills using real patients. It offers lifelike preparation and has more relevance to the trainee’s future (Reference SpencerSpencer, 2003), i.e. their day-to-day performance as a doctor. The learning occurs within context on real patients and is therefore easier to recall (Reference Hartley, Gill and WaltersHartley et al, 2003). The skills a trainee learns from one patient are transferable to contact with others (Reference Dent, Dent and HardenDent, 2001). For example, if a trainee learns competently to assess suicidal ideation in an individual with depressive disorder they may use this learnt skill for assessing suicidal ideation in people with other disorders.

Box 1 The advantages and shortfalls of patient-based teaching

Advantages

-

• Learning in context

-

• Opportunity for role modelling

-

• Teaches transferable skills

-

• Increased learner motivation

-

• Increased professional thinking

-

• Integration of clinical skills, communication skills, problem-solving, decision-making and ethical challenges

Shortfalls

-

• Its ad hoc nature

-

• Decline in availability of clinical material (patients)

-

• Cannot cover whole curriculum

-

• Poorly supervised and variable delivery

-

• Conflicting pressures of teaching and service delivery

Patient-based teaching enables direct feedback from the patient (Reference Ferenchick, Simpson and BlackmanFerenchick et al, 1997) and offers the opportunity for shadowing (see next section), in which trainees can observe a humanistic approach from an experienced clinician and learn from this (Reference Dent, Dent and HardenDent, 2001).

Numerous aspects of patient assessment and management can be taught by patient-based teaching (Reference RamaniRamani, 2003). Interpersonal skills such as empathy, sensitivity and communication can be learnt by observation and shadowing or by performance under supervision with feedback.

The General Medical Council states that ‘general clinical training is an integral part of basic medical education’, the aim of which includes the development of competence in history-taking, clinical examination, interpretation and selection of diagnostic tests, making diagnoses, decision-making and provision of treatment (General Medical Council, 1997). These basic skills are required for the processes of assessing and treating patients. The Council also requires that doctors treat patients politely and considerately; respect their dignity, privacy and rights; listen to them and respect their views; respect their right to be involved in decisions about their care; be honest and trustworthy; and respect and protect confidential information (General Medical Council, 2001). A number of authors have indicated how these skills and requirements can be learned through patient-based teaching. For example, communication skills can be practised in discussing a therapeutic intervention with a patient (Reference ReesRees, 1987; Reference Janicek and FletcherJanicek & Fletcher, 2003); clinical reasoning and decision-making (Reference Jolly, Harris, Peyton and PeytonJolly et al, 1998), clinical ethics (Reference SeiglerSeigler, 1978) and appropriate attitudes (Reference LaCombeLaCombe, 1997) can all be learned in interactions with real patients.

The dwindling patient base

Unfortunately, opportunities to teach with in-patients have been declining for some time. This might in part explain the reduced role of clinical teaching (Reference LaCombeLaCombe, 1997), which has been found to be ad hoc, often poorly supervised and dependent on the clinical material available (Reference CoxCox, 1993a ). Often only parts of the curriculum can be covered purely by clinical teaching.

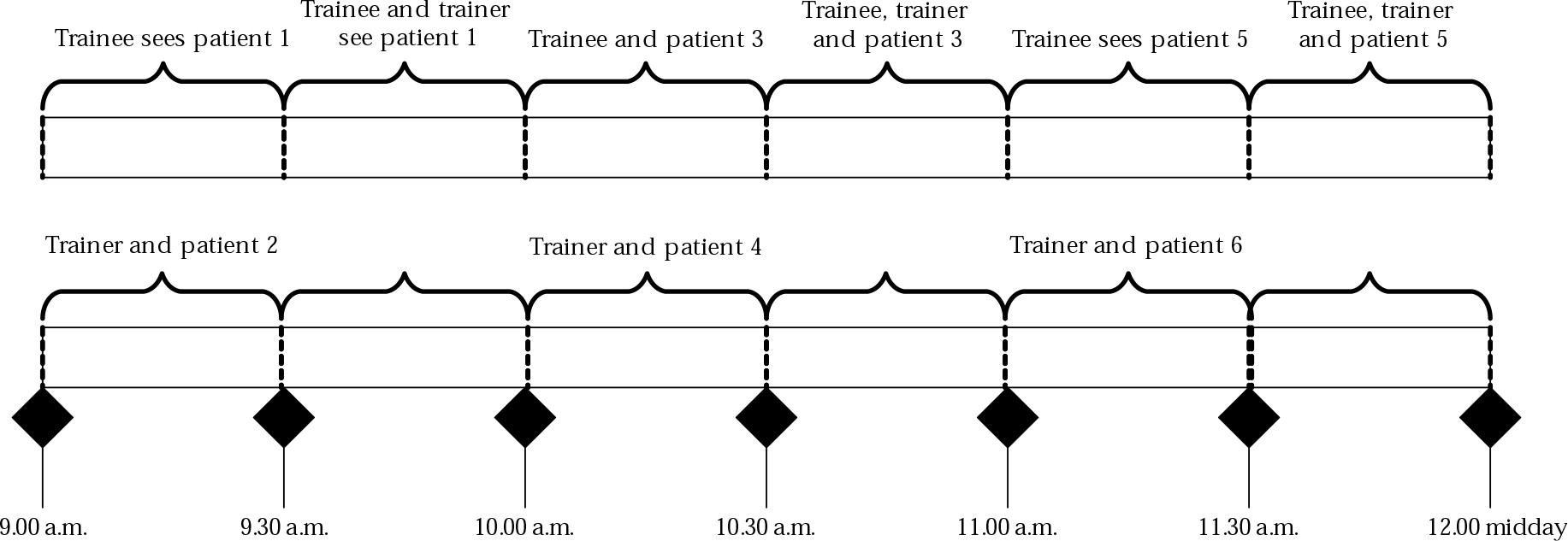

There are opportunities for patient-based teaching in community settings but this is not easy to observe and supervise. Out-patient clinics also offer the opportunity but teaching can conflict with the pressures of service delivery. One way of fitting teaching time into a clinic schedule with minimal impact on the number of patients seen is to apply ‘wave scheduling’ (Fig. 1), a technique suggested by Reference Ferenchick, Simpson and BlackmanFerenchick et al(1997).

Fig. 1 Wave scheduling.

Teaching models

There are numerous ways in which psychiatrists can teach trainees using real patients (Box 2). Some methods require one-to-one sessions and others are suitable for small-group teaching.

Box 2 Models for patient-based teaching

Shadowing (role-modelling)

The trainee shadows a consultant and learns by observation

Patient-centred

The trainee is allocated patients and follows their progress from start to end of episode of illness

Reporting back

The trainee assesses the patient and reports back to the trainer

Direct observation

The trainer observes the trainee’s performance directly

Videoing interviews

The trainee’s interview with the patient is videotaped and later viewed with the trainer

Case conference

A case is presented to and discussed by a wider audience

Shadowing (role-modelling)

Shadowing or role-modelling enables trainees to learn from the behaviour of a senior clinician in consultations with patients – the clinician’s attitude to the patient, their professional approach, their handling of difficult situations and how they negotiate treatment plans. This works well in out-patient clinics and when a good example is set. Should the senior clinician not have a professional approach then the students’ learning might be misguided. Another problem with shadowing is that the learning is passive – it relies on the students’ motivation to observe and reflect on what is happening.

Patient-centred teaching

In contrast to shadowing, patient-centred teaching is an active technique in which trainees are allocated patients at the start of their placements. They assess the patients and follow their progress during treatment. They are encouraged to present their findings, interpret investigation results and be involved in discussions about patient management. They supplement what they have learnt by background reading. They are actively involved in their learning by being encouraged to review their patients regularly and contribute to ward discussions. This approach requires consultants to spend time on management.

The report-back model

In this approach, the trainee sees the patient alone for assessment, for example to take a history. They report back to the trainer, presenting their findings, their views on the diagnosis (problem-solving) and the appropriate management (judgement). They are given constructive feedback by the trainer.

Direct observation

In direct observation the trainer sits in on the trainee’s interview with a patient to observe the trainee on a set task (e.g. discussing with a patient a change of treatment). After the interview, the trainer gives feedback on the trainee’s performance. This is a useful technique for learning isolated skills but less appropriate for teaching clinical judgement or problem-solving.

Videotaped interviews

The trainee videotapes an interview with a patient (the patient’s consent is required – see General Medical Council, 2002). Later, the video (which can be paused during play) is viewed with the trainer (and perhaps with other trainees) and its content is discussed. This is a useful way of learning consultation and communication skills.

Case conferences

A case is presented to a wider (sometimes multi-professional) audience and interesting or challenging aspects are discussed.

Doing patient-based teaching

The key to a successful patient-based teaching session is good preparation on the part of the trainer. With good preparation the curriculum can be systematically covered. Topics taught are not dependent on chance, as in the traditional apprenticeship model (Reference RamaniRamani, 2003). It may seem obvious, but it is essential to define what is to be taught, to whom and how.

It is crucial to understand the trainees’ previous experience, level of competence and desired outcome. The learning needs and outcomes for a senior house officer (SHO) in the first 6 months of training are different from those of an SHO approaching the Royal College of Psychiatrist’s membership examinations. Similarly, the needs of a psychiatric trainee differ from those of a trainee for general practice. By knowing the experience and career aims of the trainee you can pitch the learning session at the right level and select suitable content to meet their needs. Planning must include anticipation of trainee numbers and required resources (e.g. how many students, how large is the room, what equipment is available and will other staff be present?).

Session design

There are two key aids in the design of sessions. One is an understanding of the experiential learning cycle (Reference KolbKolb, 1984), the four stages of which are:

-

1 concrete experience – experience of a new situation;

-

2 reflective observations – reflection on the experience;

-

3 abstract conceptualising – formation of concepts and generalisations;

-

4 active experimentation – testing the concepts in new situations.

Thus, the trainee continues to develop by learning through direct experience and reflection.

The other aid is a sound knowledge of the curriculum content. The trainer (and, indeed, the trainee) has a clear duty to be familiar with contemporary expectation.

Selection of patients

Choice of patients to be used in teaching requires careful consideration. Reference Janicek and FletcherJanicek & Fletcher (2003) emphasise attending to the patient’s comfort as the first step in teaching at the bedside. The patient’s clinical condition must not be detrimentally affected by the teaching. Selection of patients also requires that any teaching can fulfil curriculum objectives. The patient must have capacity to give consent and full consent must be obtained. Thus, they should be told what is likely to happen during the session – how many trainees to expect, what the aims of the session are, what the trainees will do, how long it is likely to take and how they can stop the session if they want to. The patient must be informed that there might be discussion that does not relate to themselves or their condition and that their confidentiality will be maintained. They can be given the opportunity to ask questions at the end of the session. It is important to clarify how they wish to be addressed during the session.

Obviously, the trainer must know the patient and their condition. Some clinicians have lists of patients who are willing to participate in training. This makes it easier to plan teaching and cover the curriculum.

Trainers worry that patients participating in teaching could find it stressful, upsetting or detrimental to their health. However, research suggests that most patients like being involved in this way (Reference WrightWright, 1974; Reference O'Flynn, Spencer and JonesO’Flynn et al, 1997; Reference Lynöe, Sandlund and WestbergLynöe et al, 1998). Patients report that they learn about their condition, feel special and experience increased self-esteem. They also value the opportunity to use their illness to benefit others.

Fictional case example

Mr. A is a 36-year-old man who was assessed by a trainee as a new patient in an out-patient clinic. He presented with low mood and symptoms of anxiety. Investigations reveal that his gamma-glutamate (γ-GT) level is markedly raised. He is due to be seen by the same trainee at the next clinic and agrees for the interview to be a teaching session with the trainer present. The case has been fully discussed with the trainer, who has surmised that the most likely cause of the raised γ-GT is excessive alcohol consumption.

Aim of the teaching session

The trainee will learn how to manage a patient with raised a γ-GT level.

Objectives of the session

The first-year SHO in psychiatry will sensitively and honestly:

-

1 inform the patient of the raised γ-GT;

-

2 explain the possible causes of the raised γ-GT;

-

3 explain the implications of the raised γ-GT;

-

4 further assess the patient in the light of the results, exploring the patient’s alcohol intake, evidence for harmful or dependent alcohol use and for the social, psychological and biological sequelae of consuming excessive alcohol.

Define learning outcomes

Before beginning the teaching, the trainer should define the desired learning outcome (the aim) and set objectives for the teaching session that will achive this aim. To do this it is necessary to clarify what the trainees should gain from the teaching. What should they know and be able to do at the end of the session? How should their attitudes change? (e.g. should they improve their understanding of the impact of illness on the lives of patients and their families?). A trainer could encourage trainees to take responsibility for their own learning by asking them to set their own learning outcomes (within the context of the curriculum). This approach can enhance the trainees’ motivation to learn.

In the fictional case example above, the aim is given in a broad statement describing the general goal of the teaching and it gives rise to the objectives, specific statements detailing what will be attained in the session. Well-written objectives contain four elements:

-

• a description of the learner (in our case example, a first-year SHO in psychiatry);

-

• the behaviour that they will demonstrate (e.g. they will be able to inform the patient of the raised γ-GT);

-

• the conditions in which they will demonstrate the learning (here, in a follow-up patient with raised γ-GT);

-

• the degree to which they can do this (e.g. in a sensitive and honest manner).

These points enable the trainer to set the content and select appropriate teaching strategies for the teaching session. The resulting objectives give clear guidance to the trainee of what is expected and therefore direct their learning.

Session planning

There are principles that determine the content and sequence of any learning or teaching session. It is important not to overwhelm the trainees. Attempting to cover too much will result in little being retained. Concept mapping (Reference Lawless, Smee and O'SheaLawless et al, 1998) is useful for selecting crucial, rather than less relevant ‘of interest’, content. Concept mapping involves brainstorming all the potential content of a curriculum topic and then selecting the essential and desirable components to be taught and learnt, avoiding overlap with things that can easily be read in books.

The ‘events of instruction’ model (Reference Gagné, Briggs and WagerGagné et al, 1992) is useful for structuring sessions (Box 3). The process of learning from patients is well-described by Cox’s ‘figure of 8 sequence’ (Reference CoxCox, 1993a –h), which involves the sequential phases of experience followed by explanation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Cox’s structure for bedside teaching (Reference CoxCox, 1993a). © The Medical Journal of Australia. Reproduced with permission.

Box 3 The eight events of instruction ( Reference Gagné, Briggs and Wager Gagné et al, 1992 )

-

1 Gain the trainees’ attention – this is to arouse their interest

-

2 Inform them of the objectives – so they know what to expect and what is expected of them

-

3 Stimulate recall of prerequisite knowledge – to confirm that they have the required background knowledge for the level of the learning

-

4 Communicate stimulus material to them – give them a potted history of the patient and his or her problems

-

5 Give learning guidance – tell them how they could go about the assigned task

-

6 Elicit the performance – get the trainees to do the assigned task

-

7 Give feedback on each trainee’s performance

-

8 Enhance retention and transfer of what has been learnt – recap and reflect on each trainee’s performance and what they have learnt; recommend suggested activities to build on what they have learnt

It is a good idea to draft a plan for the session (see Reference CurzonCurzon, 1997: p. 277). This should establish a sequence for the teaching, set out the time frame and give structure to the session.

Starting the session

Before any training session begins, the trainee should be told the objectives of the session and what will be expected of them. For example, if the session involves face-to-face interactions with a patient, the trainee will be expected to be courteous and empathic. Boundaries such as the time available with the patient should be set.

Trainees will need certain theoretical knowledge before they can learn clinical skills, and the trainer should question them to ensure that they have this. Box 4 shows questions appropriate to our case example. Without such knowledge the trainee will not have a successful encounter with the patient.

Box 4 Appropriate preliminary questions relating to the case example

-

• What is the likely cause of the raised γ-GT?

-

• Is the damage permanent or reversible?

-

• Is it serious for the patient?

-

• What does the patient need to do to reverse the damage?

-

• How do you think the patient will feel on hearing the test result?

-

• How could you ease the patient’s distress?

By asking questions the trainer is also encouraging the active involvement of the trainee. People who learn actively (by doing and thinking rather than passive observation) have a deeper understanding and better retention of what they have learnt. They have increased motivation, curiosity and interest. Questioning encourages logical and analytical thinking.

Formulating questions requires skill. Generally, questions should:

-

• be short and easy to remember

-

• be stated in easy-to-understand language

-

• be unambiguous

-

• be appropriate to the level of the learner

-

• encourage recall of fact and problem-solving

-

• allow adequate time for an answer.

If the trainee gives a poor answer they can be gently corrected, given hints, offered prompts and provided with explanations to find the solution. They could be asked further questions that enable them to work through to a better answer.

Explanations may be interpretive (explaining what), descriptive (explaining how) and reason-giving (explaining why) (Reference Brown and AtkinsBrown & Atkins, 1988). They are important and they work best when the information is given in small chunks and expressed in clear language.

It is important to enhance and maintain the trainee’s motivation by being supportive, approachable and non-judgemental. According to Reference Newble and CannonNewble & Cannon (2001), good teachers are those that are friendly, helpful and understanding. Trainees should be praised for correct responses because success breeds success. Humiliation has the opposite effect.

During the session

What happens during the session will depend on the teaching model being used. For example, in direct observation, the patient and trainee will be introduced to each other and the trainer will then observe as the trainee performs a set task such as explaining an abnormal blood test result to the patient.

Ending the session

At the end of sessions involving patients, the trainee or trainer should debrief the patient, check that they are comfortable and thank them for their help. They should also be given the opportunity to ask questions. They might also be asked to give their views during the subsequent feedback stage.

It is imperative to give feedback to the trainee after the session. Constructive feedback enhances learning (Reference Rolfe and McPhersonRolfe & McPherson, 1995), and without it the learners do not know whether what they are doing is acceptable. Unfortunately, review of medical teaching has demonstrated that feedback is often badly given or not given at all (Reference Metcalfe and MatharuMetcalfe & Matharu, 1995; Reference BeckmanBeckman, 2004). Feedback should be constructive and prompt. Giving feedback should start with what has been done well, then areas that could be improved should be covered, explaining how. It should be based on specific examples. Instead of ‘You did well’ it is more helpful to say ‘You were sensitive in telling the patient about his raised γ-GT, in exploring and answering his worries and putting him at ease. This enabled you to build a good therapeutic relationship with him’. The trainee might be asked to say how they thought they did, which encourages active involvement in their learning. Reference Chambers and WallChambers & Wall (2000) give a good description of several models for giving feedback, including Pendleton’s rules.

As part of giving feedback, trainees should be encouraged to reflect on what they would and would not do given a similar encounter in the future.

After feedback, trainees should recap on what they have learnt and should be encouraged to seek clarification on aspects they have not understood. They could be informally tested to consolidate their knowledge and to confirm that they have indeed learnt something. They could also be given activities to build on what they have learnt, for example suggested reading or another patient to see.

After the session

The trainer needs to reflect on the session – what went well and what was less successful. This helps to identify what and how things might be done differently next time in order to improve their teaching.

Small-group teaching

The case example depicts a traditional one-to-one teaching session. In the future, clinical training might have a greater emphasis on small-group teaching. This can have the advantage that individuals learn not only the basic skills but also to work with others as part of a team. Trainers need to be aware of the difficulties of small-group teaching and strategies to deal with them. A particular problem arises during sessions where one trainee is performing the task and the others are observing. It is common for the observers to ‘switch off’ and become passive on-lookers. They can be actively involved by being set specific tasks, for example to give feedback at the end. Difficulties can also occur with the dynamics of the group (Reference JaquesJaques, 2000; Reference QuinnQuinn, 2000) and some suggestions for dealing with these are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Strategies to deal with problems of group dynamics during small-group teaching (Reference QuinnQuinn, 2000)

| Problem | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Hogging the limelight | Praise the individual for input and request that others are given a chance to answer. Invite others to comment |

| Everyone speaking at once | Praise them for wanting to contribute, exert control, try to use humour |

| Conflict within the group | Accept that people have different views. Remind members to question theories and not individuals |

| Reluctance to participate | Build each individual’s confidence, gently encourage participation, ask the group members to take it in turn to contribute |

Conclusions

Recommendations based on recent review of postgraduate medical education in the UK will change the way in which trainees learn. There is likely to be a fundamental shift from the apprenticeship model of learning towards a training based on well-planned, systematic, curriculum-based teaching sessions. The skills learnt will be subject to workplace assessments, with successful trainees graduating from one level of training to the next. There will be increasing levels of supervision, direct observation and assessment of trainees as they work.

Learning based on patient contact will remain at the core of medical education, and a patient-based approach in medical training will enable trainees to develop professional and humanistic skills as well as medical knowledge. However, the decreasing clinical opportunity for patient-based teaching within in-patient settings requires that training be more community-based, in out-patient clinics, day hospitals and even specially developed units. One solution to the conflict between the pressures of service provision and the delivery of good-quality training would be for rotation organisers to run small, patient-based teaching groups rather than traditional one-to-one clinical sessions.

Trainers will need particular skills in both planning and teaching. The full curriculum must be covered and the educational cycle will incorporate preparation, planning, feedback and evaluation. To ensure the quality of the teaching they deliver, trainers will themselves need formal training. Units may even consider the creation of specialist consultant posts for teaching.

MCQs

-

1 Outcome-based education:

-

a includes development of skills for lifelong learning

-

b emphasises the results of knowledge-based assessments

-

c is not simply concerned with what a doctor does (the performance of tasks)

-

d includes standards of professionalism

-

e will require greater development of workplace assessments.

-

-

2 Professionalisation of teaching:

-

a emphasises formal learning for those with teaching responsibilities

-

b refers to the payment system for clinical tutors

-

c is irrelevant to the modernisation of medical education

-

d includes the accreditation of those with teaching responsibilities

-

e requires clear dedicated time for teaching in job plans.

-

-

3 In lesson-planning:

-

a concept mapping is a useful technique

-

b overlaps with book reading are essential

-

c clear aims and objectives are essential

-

d include time for giving feedback

-

e establishing the learners’ prior knowledge is unimportant.

-

-

4 In small-group teaching:

-

a group dynamics are unimportant

-

b some students require encouragement to voice their ideas

-

c conflict is essential to the learning process

-

d the facilitator acts as expert and imparts their knowledge

-

e patient-based activities are not possible.

-

-

5 In patient-based teaching:

-

a it is important to be well prepared

-

b you can involve any patient in teaching

-

c patients suffer from the teaching

-

d trainees learn best by being humiliated

-

e trainees learn best by active teaching methods.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | T | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | F | c | F |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.