Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is the evidence-based treatment of choice for several psychiatric disorders, and it is agreed that a person's age should not preclude them from psychological therapies (Department of Health, 2002). The proportion of the UK population aged 65 or older (the most common definition of old age) continues to rise and the question of how best to meet the CBT needs of this age group becomes increasingly relevant. Inherent in the CBT model is a focus on the needs of the individual and a flexible, collaborative approach. However, there are modifications to the structure and content of therapy that are more likely to be required when working with older people. The aim of this article is to provide the reader with an overview of these modifications.

What is CBT?

Aaron T. Beck developed the cognitive–behavioural therapeutic model in the 1970s, having been a psychoanalyst for many years. While practising as an analyst, he discovered that his clients had streams of unreported thoughts that frequently preceded an unpleasant emotional state. Furthermore, these ‘automatic thoughts' could be brought to conscious attention. It was this discovery that eventually led to the development of CBT (Reference BeckBeck, 1976).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy shares qualities with other psychotherapeutic approaches, but there are fundamental differences. The rationale of the therapy is based on a cognitive model of emotional disorders which, in its simplest form, proposes that an individual's mood and behaviour are determined by the way he or she perceives the world. This world view, in turn, depends on cognitions that are based on underlying assumptions and core beliefs derived from previous experiences (Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck et al, 1979). Emotional problems putatively have their origins in distorted cognitions and their corresponding underlying dysfunctional assumptions and core beliefs, which become activated at times of difficulty or stress. Crucially, the cognitions are held to occur in conscious thought and are therefore more accessible and amenable to modification. This contrasts with classic psychodynamic psychotherapy or behavioural therapy, where the content of conscious thought is considered less significant (Reference BeckBeck, 1976).

In terms of style, CBT is collaborative, with focus on the therapeutic relationship as well as empathy, warmth and genuineness. It is active, directive, time limited and goal oriented, which gives it a structured, focused form. The term ‘collaborative empiricism’ has been used to describe the way the therapist and client work together to construct an individual, testable formulation of the problem, to which treatment is tailored. The therapeutic methods embrace a scientific stance aimed at identifying, reality-testing and correcting distorted cognitions to bring about long-term change in emotional state (Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck et al, 1979). To do this, clients are helped to tune in to their negative automatic thoughts and keep a thought record. This facilitates a ‘metacognitive shift’ – the ability to see one's thoughts as opinions rather than statements of fact – which allows the process of reality-testing to take place. Techniques for reality-testing dysfunctional thoughts and assumptions include in-session evaluation: examining evidence for and against, exploring the utility of the beliefs and developing alternative perspectives. Habitual patterns of thinking (cognitive distortions such as catastrophic thinking and dichotomous thinking) may be identified. Eventually, the client is encouraged to apply these techniques between sessions, using the dysfunctional thought record (Reference BeckBeck, 1995). Another powerful technique is the use of behavioural experiments to explicitly test and potentially disprove predictions that may be based on dysfunctional thinking (Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler and FennellBennett-Levy et al, 2004).

CBT with older people: the historical context

It is now widely accepted that older adults with mental health problems should have access to the same range of therapies as those people under the age of 65 (Department of Health, 2001). This has been a comparatively recent change in thinking, however. Reference Freud and StracheyFreud (1905) pronounced (when, interestingly, he was aged 49) that anyone over the age of 50 was uneducable and thus unsuitable for psychotherapy. Other key figures in the psychoanalytic movement were more interested in the impact of increasing age. Reference HorneyHorney (1942) reflected that ‘man can change and go on changing as long as he lives’. Jung was interested in ‘a psychology of life's morning and a psychology of its afternoon’ (Reference JungJung, 1929: p. 38), and his theory of archetypes includes senex, or the wise old man (Reference GarnerGarner, 2002). Erikson's eight ages of man (1966) encompass the whole life cycle, with the age of ‘ego integrity versus despair’ relating to old age and the balance between accepting one's life and negative feelings about death and degeneration. Despite the theoretical interest in the internal world of older people, it appears that Reference Freud and StracheyFreud's (1905) prejudicial view has been highly influential.

The seminal texts on CBT by Beck and his colleagues (Reference BeckBeck, 1976; Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck et al, 1979) contain no reference to the age of clients. This could be interpreted as meaning that the approach could be used irrespective of the patient's age. Equally, one could argue that the omission of specific reference to issues of age shows implicit agreement with the prevailing view from psychoanalysis (bearing in mind Beck's psychoanalytic background) that older people cannot benefit from psychotherapy. It is worth noting that in the outcome studies reviewed in Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck et al(1979), the oldest participant is aged 53, suggesting that CBT was not frequently used with older adults at that time.

That said, relatively soon after the publication of these earlier works, the specific utility of CBT as a treatment for older people was being discussed in the literature in both the USA (Reference Emery, Emery, Hollon and BedrosianEmery, 1981) and the UK (Reference ChurchChurch, 1983). Outcome research focusing on CBT with older people seems to have lagged behind that for younger adults by about a decade. The first studies evaluating CBT for depression in older people appeared in the early to mid 1980s (e.g. Reference Steuer, Mintz and HammenSteuer et al, 1984). Studies evaluating CBT for generalised anxiety disorder in older adults did not emerge until the late 1990s (e.g. Reference Stanley, Beck and GlasscoStanley et al, 1996). In a literature review, Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Dick-SiskinLaidlaw et al(2003) concluded that there is good evidence showing cognitive therapy to be a very effective treatment for depression in later life, even though differences are not always apparent between different psychological treatments. There is also an increasing evidence base for the effectiveness of CBT in the treatment of anxiety disorders in old age (e.g. Reference Barrowclough, King and ColvilleBarrowclough et al, 2001; Reference Stanley, Beck and NovyStanley et al, 2003).

The current state of the art regarding CBT and its use with older people has been summarised by Reference Koder, Brodaty and AnsteyKoder et al(1996):

‘[T]he debate is not whether cognitive therapy is applicable to [the] elderly … but rather how to modify existing cognitive therapy programmes so that they incorporate differences in thinking styles in elderly people, and age-related adjustment’.

Chronological age alone is not a helpful marker for deciding whether modifications are necessary – people over the age of 65 are a highly heterogeneous group. That said, there are issues more commonly associated with older age that, if present, may necessitate modification of therapy. These potential modifications (Box 1) will now be discussed, grouped according to their impact on the procedures of therapy (i.e. the ‘nuts and bolts' that allow therapy to happen) or the content of therapy (case conceptualisation, key cognitions, the client–therapist interpersonal process). Inevitably there is a degree of overlap between these areas.

Box 1 Procedural modifications

Tackling cognitive changes

-

• Repeat and summarise information

-

• Present information in multiple modalities

-

• Use folders and notebooks

-

• Consider offering memory training

Tackling sensory impairment

-

• Help to correct it where possible

-

• Prepare written materials in bold print

-

• Use tape recorders

Physical health

-

• Agree realistic goals

-

• Tackle dysfunctional beliefs that limit activity

-

• Input from a ‘medicine for the elderly’ team

Therapy setting and format

-

• Be flexible

-

• Consider using an outreach approach

-

• For each client consider the merits of group v. individual CBT

Procedural modifications

Addressing cognitive changes

Certain changes to cognitive functioning occur with advancing age but they are not the universal phenomena that they are widely held to be. Working memory, as measured by performance on the digit span task, shows a small but significant decline in old age. This may be because older people have poorer encoding or retrieval strategies but it has been shown that memory-trained older people can outperform younger people. Ability on sustained attention tasks is well preserved in old age but tests of selective attention show a decline. These findings are reflected in the fact that ‘fluid intelligence’ (the ability to acquire and manipulate new information, i.e. ‘wit’) declines with age whereas ‘crystallised intelligence’ (the cumulative product of information acquired as a result of fluid intelligence, i.e. ‘wisdom’) does not (Reference O'BrienO'Brien, 1999). However, it is essential to remember the issue of variability – older people have been shown to vary more on a variety of cognitive measures than younger people.

Given this information it is essential during the initial assessment for CBT to be aware of these potential problems and possibly to use cognitive screening tests (e.g. the Mini Mental State Examination, MMSE). Where problems exist it may be necessary to repeat and summarise information to enhance encoding and, for the same reason, to present information in multiple modalities (e.g. on dry-wipe boards, using audio-visual equipment) and provide folders and notebooks to record information from the sessions. It may also be useful to incorporate specific memory-training techniques.

Addressing sensory impairment

Between 50 and 75% of people over the age of 70 have hearing problems (Reference Stuart-HamiltonStuart-Hamilton, 1994). The most common form is presbycousis – loss of perception of high-frequency sounds. The incidence of visual impairment increases with age and there are several potential causes. The ageing lens of the eye loses its focal variability, resulting in presbyopia (long-sightedness), which may make reading difficult. Cataracts, glaucoma and macular degeneration are also increasingly common with age.

It will obviously be desirable to help address any sensory problems that are affecting the progress of therapy, so that the best use of time can be made. Presbycousis and presbyopia may be dealt with by encouraging clients to obtain or use hearing aids or spectacles, and it may be necessary to explore and challenge stigma-related beliefs about using them (Reference Van den Brink, Wit and KempenVan den Brink et al, 1996). Hearing problems attributed to old age could in fact have other, easily remediable causes such as conductive deafness owing to earwax. Where impaired vision cannot be corrected, written materials can be provided in large, bold print. Tape recorders can be used where visual impairment is severe.

Addressing physical health problems

Many older people enjoy good physical health, and where health problems are present they may not have a significant limiting functional effect. That said, the incidence of physical illness and disability (e.g. arthritis, cerebrovascular accident, Parkinson's disease) increases exponentially with age. Health problems can limit a client's understanding, recall or application of therapeutic principles. Physical disability may limit a client's ability to engage in behavioural experiments, or make it difficult for them to attend traditional out-patient settings for therapy.

It is essential to find a balance between remaining attentive to any physical limitations a person may have and awareness that individuals may have excessively negative appraisals of their limitations. Problems with attention and recall can be addressed as described above. Realistic goals need to be agreed for behavioural experiments and, where patients are severely limited by physical problems, it may be useful to spend more time examining dysfunctional thoughts and assumptions that may be preventing them from making the most of ongoing activities. An interdisciplinary approach with input from ‘medicine for the elderly’ teams can be very helpful in trying to assess and optimise physical functioning and thus maximise gains from therapy. A flexible approach is key and this extends to the setting of therapy, which is discussed in the next section.

Setting and format for therapy

Psychological therapies have traditionally been delivered in out-patient settings and, less commonly, to in-patients on psychiatric wards. Reference CuijpersCuijpers (1998) suggests that elderly people's access to these therapies could be improved by using psychological outreach services that offer treatment in community settings. More recent studies of the effectiveness of CBT for older people frequently offer flexibility with regard to the setting of therapy – seeing people in their own homes (e.g. Reference Barrowclough, King and ColvilleBarrowclough et al, 2001; Reference Stanley, Beck and NovyStanley et al, 2003) or in primary care clinics (Reference Stanley, Beck and NovyStanley et al, 2003). This improves access to CBT for older people with physical health problems and disabilities.

The effectiveness studies are often conducted using group, rather than individual, therapy (Reference LaidlawLaidlaw, 2001). Reference Wetherell, Gatz and CraskeWetherell et al(2003) advocate the group approach for older people because it may enhance outcome for those who are lonely or socially isolated. However, a meta-analysis of studies of CBT for late-life depression by Reference Engels and VerneyEngels & Verney (1997) revealed evidence of increased efficacy for the individual rather than group format. This raises the possibility that some older people, viewed as (and perhaps assumed to be) isolated and lonely, are being treated in group settings when they could derive greater benefit from individual therapy. Obviously, it is important to establish the client's preference.

Modifications to therapy content

When working with older people, there are certain age-related themes and factors that may emerge more frequently and thus require a modified focus in terms of the content of therapy (Box 2). In this context, ‘content’ refers to issues such as case conceptualisation, key cognitions and themes, as well as client–therapist ‘interpersonal process issues' (see below). These can all have an important bearing on the progress and outcome of therapy.

Box 2 Modified therapy content

Case conceptualisation

-

• Cohort beliefs

-

• Role investments

-

• Intergenerational linkages

-

• Physical health

Key cognitions

-

• Loss and transition points

-

• Attitudes to ageing and ageism

-

• Health anxiety

Client beliefs

-

• ‘Too old to change’

-

• Prejudice against younger therapist

-

• Passivity

-

• Dependence

-

• Stigma

Therapist beliefs

-

• Ageist assumptions

-

• Therapeutic nihilism

Modified case conceptualisation

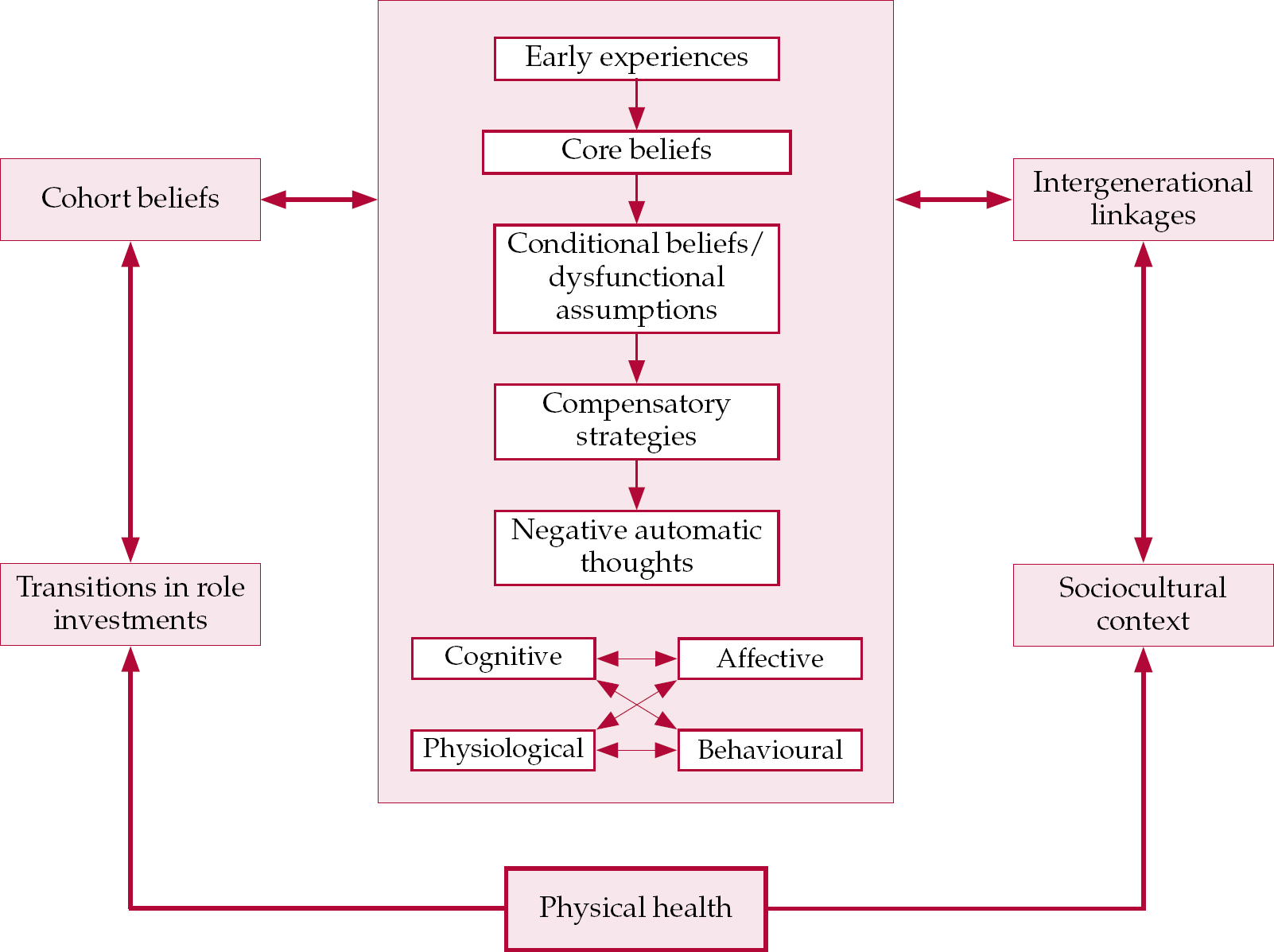

A case conceptualisation, shared between client and therapist, is one of the cornerstones of CBT. A case conceptualisation is an idiosyncratic representation of the patient's current problems, including predisposing and maintaining factors (cognitive, behavioural, emotional, interpersonal). It enables the therapist and patient to develop problem-specific treatment interventions. Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-ThompsonLaidlaw et al(2004) have argued that standard CBT conceptualisations are inadequate to describe the complex age-specific issues that face older adults, and they have proposed an alternative model (Fig. 1). This builds on Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck's (1979) model, to include information thought to be important and necessary when working with older people: cohort beliefs, role investments, ‘inter-generational linkages’, sociocultural context and physical health.

Fig 1 Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-ThompsonLaidlaw et al's (2004) CBT conceptual framework for older people.

Cohort beliefs

These are beliefs held by groups of people born in similar time periods, reflecting shared experiences. These experiences can have a significant impact on the therapeutic process, and combining cohort beliefs with core beliefs provides an age and generational context to therapy work.

Role investments

Role investment describes the extent to which an individual remains involved in personally meaningful, purposeful and relevant activities and interests. It has been proposed that vulnerability to depression may be related to the degree of investment in these roles. Old age may represent a time of transition in these areas of investment and self-validation, which may function as a trigger for emotional problems.

Intergenerational linkages

This issue draws attention to the apparently increasingly dynamic role that grandparents and great-grandparents play in society and, in particular, families. With this comes the potential for tensions and disagreements in the context of intergenerational relationships. There may be interaction here with cohort beliefs, for example relating to notions of family structure, roles, etc.

Sociocultural context

The sociocultural context refers in particular to people's attitudes to their own ageing and may include internalised negative stereotypes about growing old. It is important that therapists take their own values into account.

Physical health

It is advocated that the therapist asks about the presence of physical illness in the patient and explores the patient's understanding of diseases and resulting outcomes.

Modified focus on key cognitions

Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-ThompsonLaidlaw et al's (2004) model is consistent with the idea that certain themes are more likely to emerge in the dysfunctional belief systems of older individuals in therapy. Some commonly encountered themes will now be discussed.

Loss and transition points

Reference ThompsonThompson (1996) has argued that the problems that commonly bring older people into therapy can be distilled down to the twin themes of loss and transition points. The theme of loss includes bereavement (spouse, other family members, friends) and loss of social networks (through bereavement or changes in social situation, e.g. relocation to a new community). Furthermore, physical illness can be viewed as a loss of health. Transition points include experiences such as retirement, but may also include changes in the context of intergenerational relationships or role investments, as discussed above. Such events may trigger depressogenic thoughts of missed opportunities or unresolved relationships, and reflection on unachieved goals (Reference ThompsonThompson, 1996). Reference WilkinsonWilkinson (1997) proposes that cognitive distortions typical of depression in older people reflect a difficulty in adapting to losses. The key to helping the client work through these issues is to identify the personal meaning of the loss or transition point and to look for any cognitive distortions or dysfunctional thinking on which that meaning may be based. The eventual aim is to identify alternative, more adaptive ways of thinking about the situation, thus enabling the individual to adjust.

However, in viewing depression as a natural consequence of these losses, Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Dick-SiskinLaidlaw et al(2003) advise guarding against the ‘fallacy of good reasons' or ‘understandability phenomenon’ – the notion that depression in older people is in some way to be expected as a normal part of ageing.

Ageing and ageism

An older person's attitude to and beliefs about age-ing commonly require attention in therapy. Ageism is not uncommon in our societies and there is a risk that older people may internalise negative judgements and ageist stereotypes that may lead them to adopt restrictive patterns of behaviour consistent with these beliefs. It is not difficult to see how beliefs such as ‘growing old is a terrible thing’ or ‘old age inevitably means loss and decrepitude’ could have depressogenic potential, and in an already depressed individual could deepen feelings of helplessness and poor self-esteem (Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-ThompsonLaidlaw et al, 2004). Problems can also stem from the catastrophising of normal age-related changes (see next section). It is important to remember that older people are not necessarily passive victims of ageism. Reference Hepple, Hepple and SuttonHepple (2004) emphasises their potential to hold ageist beliefs towards both their peers and younger people (reverse ageism), and proposes that ageism can be viewed as an interchange between ‘the young’ and ‘the old’ rather than a series of prejudices in the minds of the ‘persecuting young’ alone.

In therapy, the aim should be to highlight the arbitrary nature of age-related beliefs. It may be useful to challenge myths regarding ageing by providing accurate information in the form of books and documents that draw on research findings (e.g. Reference Rowe and KahnRowe & Kahn, 1998; World Health Organization, 1999). It has been argued that the approach of collaborative empiricism inherently challenges stereotypes of older people as ‘useless, helpless, uninteresting’ (Reference Steuer and HammenSteuer & Hammen, 1983: p. 286).

Health anxiety

Another issue that may feature frequently in the depressive cognitions of older people relates to physical symptoms and physical illness. Reference WilkinsonWilkinson (1997) argues that, in therapeutic work with older people, ‘skills for assessing and managing physical symptoms are essential’ and raises the point that physical symptoms may arise from physical or psychological disorders, or may be of unknown origin. Cognitive–behavioural therapy can potentially help in two main ways. First, older people may be less likely to acknowledge that symptoms such as loss of energy and appetite may be a manifestation of a depressive disorder. Thus, Socratic questioning and education about these issues may facilitate understanding and treatment (Reference Koder, Brodaty and AnsteyKoder et al, 1996). Second, older people with depression and comorbid physical illness may ruminate about disability and develop overdeveloped expectations of eventual incapacity. The role of CBT is to identify and tackle cognitive distortions that may be feeding this process, and to help patients differentiate between the hopelessness and helplessness of depression and a realistic, yet hopeful, recognition of limitations (Reference Emery, Emery, Hollon and BedrosianEmery, 1981).

Modified focus on client–therapist interpersonal processes

There is sometimes a perception that there is no place in CBT for consideration of the dynamics of the therapeutic relationship. However, Reference Beck, Rush and ShawBeck et al(1979) discuss the impact of transference and countertransference in CBT. More recently, the term ‘interpersonal process issues' has been used to describe the patient's reactions to the therapy and therapist, as well as the therapist's reactions to therapy and the patient, in the context of CBT (Reference Safran and SegalSafran & Segal, 1996). Process issues are particularly relevant when they block progress in therapy, and some common themes when working with older people will now be discussed.

Beliefs that may interfere with therapy

The patient's beliefs

It is often suggested that older people may believe that they are ‘too old to change’. This belief may be derived from a combination of internalised negative stereotypes of old age as well as cohort beliefs. As a result, older people may not seek help for their difficulties and, if help is sought, they may have reduced expectations of treatment outcomes (Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Dick-SiskinLaidlaw et al, 2003). Reference WilkinsonWilkinson (1997) emphasises the need to challenge this belief from the outset of therapy and suggests provision of information on changes in learning capacity with age. Another potential influence of ageism (in the form of stereotypical prejudice against ‘the young’) is that age discrepancy can lead older people to question their therapist's empathy and skill (Reference ThompsonThompson, 1996).

Reference Steuer and HammenSteuer & Hammen (1983) describe passivity as another potential problem in this context. Older people may believe that being a patient involves ‘passive receptiveness of the expert's help’ (p. 294). They suggest that older patients need to be encouraged to actively generate and enact new behaviours and strategies for themselves and not just ask for recommendations. In essence, the collaborative nature of CBT needs to be reinforced consistently. A related issue is that of dependency. Older people who have suffered bereavements may be more lonely and isolated and therefore there may be greater potential for dependence in the therapeutic relationship. Dependency issues may inhibit therapy if a client attributes therapeutic benefit directly to the therapist, and ending therapy may be problematic. Some strategies for dealing with dependency are listed in Box 3.

Box 3 Strategies for dealing with dependence on the therapist

-

• Emphasise the time-limited nature of therapy from the outset

-

• Explicitly discuss the issue as part of the shared case conceptualisation

-

• Encourage clients to attribute improvements to their own efforts

-

• End therapy gradually; establish together how the therapist can be replaced in the client's support system

Another potential source of impedance in therapy is older patients' beliefs regarding the stigma of mental health problems (Reference WilkinsonWilkinson, 1997; Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-ThompsonLaidlaw et al, 2004). Reference Lebowitz, Niederehe, Birren, Sloane and CohenLebowitz & Niederehe (1992) state that ‘the stigma of mental illness is especially strong in the current cohort of elderly people, who tend to associate mental disorder with personal failure, spiritual deficiency, or some other stereotypic view’. Many older people have stereotypical prejudices regarding ‘therapy’ and ‘therapists' and have been coerced into or ‘sent’ for therapy. Such individuals may be ambivalent about psychological approaches or the idea of a collaborative relationship. It is useful to normalise these ideas so that they can be explored and, if necessary, challenged. Many myths and assumptions regarding therapy will be dismissed during the process of educating the client about the CBT model and the progression of therapy itself.

The therapist's beliefs

Padesky states that the ultimate efficacy of CBT is enhanced or limited by the beliefs of the therapist (Reference JamesJames, 2004). Thus, when working with older people, therapists must be aware of their own ageist assumptions. Reference Emery, Emery, Hollon and BedrosianEmery (1981) lists as common dysfunctional beliefs: ‘old people can't learn new behaviours’; ‘the elderly are inadequate and need to be cared for’; ‘there is something inherently inferior about old age’; ‘they are going to die soon so why bother?’ In addition, a therapist's stereotypical views of elderly people may result in blaming the client for being ‘unable to engage in therapy’, ‘unpsychologically minded’ or ‘cognitively impaired’ (Reference Charlesworth and GreenfieldCharlesworth & Greenfield, 2004). It is easy to see how these types of beliefs, if left unchallenged, can lead to a sense of therapeutic nihilism.

As part of the broader process of being aware of their assumptions, therapists (whether in session, listening to therapy tapes or in supervision), should pay attention to the presence of ageist assumptions. Reference JamesJames (2004) emphasises the fact that therapists who do hold stereotypical views of age can use the cognitive approach to tackle their unhelpful beliefs. Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-ThompsonLaidlaw et al(2004) suggest that therapists ask themselves whether they would accept this belief as fact in a younger patient and also whether they would accept in someone younger the limitations this person places on the expected outcome of therapy.

Reference Hepple, Hepple and SuttonHepple's (2004) interpersonal view of ageism is particularly relevant when considering these issues, and he argues that ‘there is a need to get beyond ageism and reverse ageism … before real communication, support and healing can take place’ (p. 62).

Remember the individual

The aim of this article has been to give an overview of how CBT can be used with older people, and the modifications to therapeutic procedure and content that may be helpful when working with this age group. There has been a trend in recent years to develop ‘manualised’ forms of CBT aimed at specific disorders. A discussion of modifications to CBT on the basis of age is at risk of falling into the trap of sounding like a CBT manual to be rigidly applied to people who happen to have reached a certain age, and thus losing sight of one of the central tenets of the therapy – a constantly evolving idiosyncratic conceptualisation of the individual's problems. The modifications discussed in this article are not meant to be applied in a rigid fashion. They are intended to inform the therapist, and may be useful if there are difficulties progressing in therapy. Ultimately, it is up to individual therapists to find their own approach to working with older clients, but they will certainly need to be aware of their own age-related beliefs and assumptions.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 Cognitive–behavioural therapy:

-

a was developed by Jung

-

b discourages client–therapist collaboration

-

c usually lasts several years

-

d involves constructing a ‘testable’ conceptualisation of the client's problems

-

e involves behavioural experiments not aimed at cognitive change.

-

-

2 When modifying CBT for older people:

-

a repeating information in different modalities may enhance encoding

-

b written materials are not appropriate for people with visual impairments

-

c clients unable to attend out-patient clinics are unsuitable for CBT

-

d a group approach is preferable

-

e physical health problems need not be considered.

-

-

3 In Laidlaw's model of case conceptualisation for older people, the following issues are considered:

-

a genetic linkages

-

b MMSE score

-

c physical health

-

d cohort studies

-

e transference.

-

-

4 Key cognitions in older people may more commonly include beliefs regarding:

-

a omnipotence

-

b Oedipal conflict

-

c countertransference

-

d transition points

-

e initiative v. guilt.

-

-

5 Interpersonal process issues in CBT:

-

a are the main focus of therapy

-

b do not apply to older people

-

c do not include an older person's attitude to a younger therapist

-

d are not influenced by stigma

-

e may include the therapist's ageist assumptions.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | F | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | T | d | F |

| e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.