The need for doctors to take on management and leadership roles within the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK has gained increasing recognition among the medical profession as well as policy makers. The report Educating Tomorrow's Doctors identified leadership skills as essential for future doctors (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2008). The final report of Lord Darzi's NHS Next Stage Review has had the most significant impact on pushing the leadership agenda for doctors. Darzi stressed the importance of developing clinical leadership in order to provide a quality service in the NHS (Professor the Lord Darzi of Denham 2008).

At the time of Lord Darzi's review, Reference Clark and ArmitClark & Armit (2008) conducted semistructured interviews with postgraduate deans and the deans of medical schools across the UK, looking at the extent to which leadership and management training were covered in the undergraduate and postgraduate curricula. They found that management and leadership skills were not considered part of undergraduate medical training in the UK, where the focus was on the clinical skills needed to be a competent doctor. However, many elements of leadership, such as self-awareness and team working, were taught under headings such as professional development. At the specialty training stage, although specific programmes on leadership and management are available, many doctors do not access them until the final 6 months of their training.

There is a long history of encouraging doctors to engage in leadership and management activities. The Griffiths Report, which introduced general management into the NHS, identified the need to involve doctors in the day-to-day management of the service (Department of Health and Social Security 1983). The first systematic attempt to involve doctors in management was in the early 1980s, with the Resource Management Initiative introduced during the government of Margaret Thatcher (Reference Packwood, Keen and BuxtonPackwood 1991). Subsequent initiatives to engage more doctors in leadership and management have included the appointment of national clinical directors at the Department of Health, the establishment of directorates across NHS trusts and Scotland's NHS boards, clinical and medical director posts in hospitals and the creation of practice-based commissioning in primary care (Reference Clark and ArmitClark 2008). The success of these programmes has been variable. Reference HamHam (2008) postulates that this is due to the poor resources put into medical leadership and limited recognition for doctors who take on leadership roles. However, the situation now appears to be changing again, with the introduction of a number of new initiatives designed to encourage junior doctors into leadership. These include the Fellowships in Clinical Leadership Programme (formerly Darzi Fellowships) and the Prepare to Lead programme offered by NHS London (2011a,b), and the Medical Leadership Programme offered by the NHS North West Deanery (2011).

Why do we need medical leaders?

Leadership is a key part of a doctor's work, and the General Medical Council (2009) Good Medical Practice (para. 42) requires that all doctors responsible for leading a team must follow the guidance in Management for Doctors (General Medical Council 2006). Doctors frequently lead healthcare teams and command considerable clinical resources. As pointed out in the Medical Leadership Competency Framework, they have a legal duty broader than any other health professional and therefore have an intrinsic leadership role within health services (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010: p. 6). Medical leadership is not just about being seen as a leader. It is about developing personal qualities such as self-awareness, self-management and integrity. Developing an ability to work effectively with others is crucial – ‘followership’ is as essential as leadership.

A number of studies have demonstrated the positive link between engagement of clinicians in leadership and improved patient care. Healthcare systems are able to achieve better outcomes, greater ease of use and better value for money for patients when clinicians are involved in the change process (Reference BerwickBerwick 1994). A medical perspective is vital in developing a broader healthcare policy that is more evidence-based and ultimately delivers patient safety and quality improvement rather than just focusing on political ideology or economic convenience (Reference Callaly and MinasCallaly 2005; Reference CarruthersCarruthers 2007). Clinicians can be effective agents of change and can play an influential role as its promoters or inhibitors (Reference Fitzgerald, Lilley and FerlieFitzgerald 2006). International evidence has demonstrated that lack of medical engagement presents significant problems to the organisational pursuit of change and improvement (Reference Dickinson and HamDickinson 2008; Reference HamHam 2008).

The NHS, particularly in England, is growing increasingly business-like and commercial in its approach. Foundation trust status offers hospitals greater autonomy, while initiatives such as world-class commissioning and the introduction of tariff systems such as payment by results (PbR)Footnote † require healthcare services to respond to market forces. For any commercially viable organisation, it is important that all of its players are on board and in tune with the organisation's vision. The complex nature of the NHS means that leadership is needed at different levels and not simply at the top (Reference Dickinson and HamDickinson 2008). This should include junior doctors playing a key leadership role in their local organisation. According to Bruce Keogh, medical director of the NHS, ‘Junior doctors are the best agents for change in our devolved NHS’ (Reference HawkesHawkes 2009). However, to invest in their leadership and managerial development will require a significant shift in culture and will be financially challenging.

Given the current economic climate, there is a need for clinical services to be delivered in a fundamentally different way so as to improve productivity and efficiency. The NHS is looking to clinicians to provide leadership in delivering services in an innovative and radically different fashion (Reference HamHam 2009).

The Medical Leadership Competency Framework

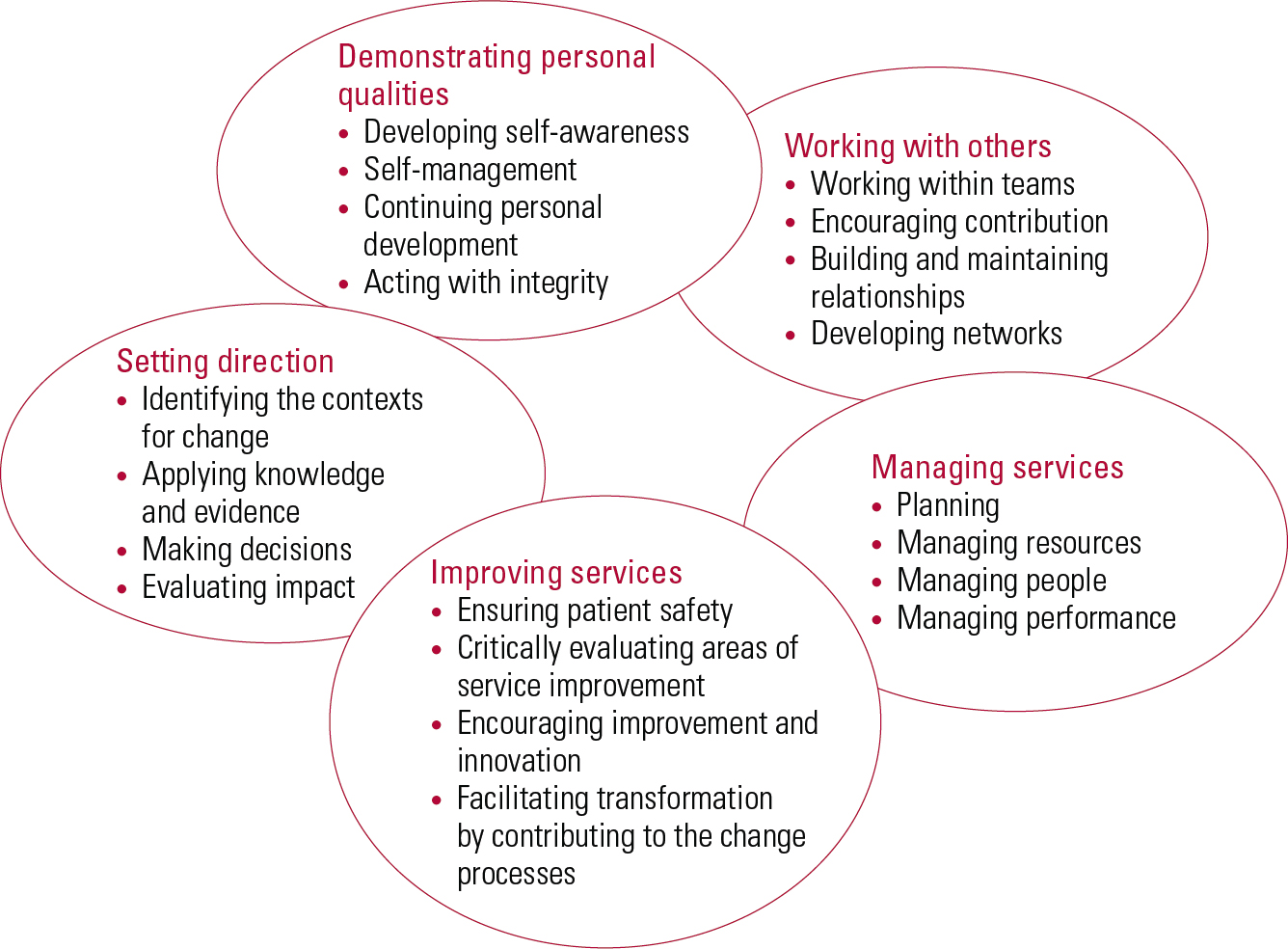

The Medical Leadership Competency Framework, introduced in May 2008, describes the leadership competencies doctors need to become more actively involved in the planning, delivery and transformation of health services (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010). The framework, developed jointly by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AoMRC) and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement applies to all doctors and medical students. It is built on the concept of shared leadership and a shared sense of responsibility for the success of the organisation and its services. The framework has five domains, with four elements in each domain (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Medical Leadership Competency Framework (after NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010, with permission).

The basic professional training period is seen as a critical time for encouraging leadership and management skills in doctors, as training during this period sets their attitudes for the future (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2007).

The 2010 core and specialty curricula

The Royal College of Psychiatrists has acknowledged the leadership needs of doctors, and the newly revised curriculum for specialist training in psychiatry reflects this (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/training/curriculum2010.aspx). The Medical Leadership Competency Framework is embedded in the new curriculum and being a manager is identified as a core competency.

The revised curriculum is structured under the seven CanMED headings (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada 2005):

-

• medical expert

-

• communicator

-

• collaborator

-

• manager

-

• health advocate

-

• scholar

-

• professional.

The curriculum explicitly states that psychiatrists are integral participants in healthcare organisations, responsible for organising sustainable practices, making decisions about allocating resources and contributing to the effectiveness of the service. Apart from the generic skills that trainees need, such as collaboration, team working and time management, the curriculum lists developing appropriate leadership skills as a learning outcome. The revised 2010 core curriculum requires that trainees demonstrate an understanding of the relationship between clinical leadership and clinical responsibility (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010a). The specialist modules of the curriculum are more explicit in specifically listing the knowledge trainees have to acquire to achieve competency in leadership skills (Box 1). A shortcoming of the curriculum is that it fails to incorporate the personal qualities needed by a leader which are part of the Medical Leadership Competency Framework.

BOX 1 Leadership skills in the specialist modules of the psychiatry curriculum

Each of the curriculum's specialist modules includes learning outcomes related to the development of appropriate leadership skills. The list below is from the old age psychiatry specialist training module.

-

• Demonstrate an understanding of the differing approaches and styles of leadership

-

• Demonstrate an understanding of the role, responsibility and accountability of the leader in a team

-

• Understand and contribute to the organisation of urgent care in the locality

-

• Demonstrate an understanding of the structures of the NHS and social care organisations

-

• Demonstrate an understanding of organisational policy and practice at a national and local level in the wider health and social care economy

-

• Demonstrate an understanding of the principles of change management

-

• Understand the principles of identifying and managing available financial and personnel resources effectively

-

• Identify the social, epidemiological and demographic processes associated with an ageing population and apply this knowledge to service development and delivery

(Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010b: pp. 87–89)

Competencies in action

How should trainees go about achieving the leadership competencies set out in the curriculum? Core psychiatry training already enables trainees to develop skills in listening, communicating, leading and enabling teams, which are some of the basic tenets of leadership. The revised curriculum makes it incumbent upon trainees to develop these leadership skills further. Organisational knowledge, financial acumen, strategic planning, conflict resolution and negotiation skills are some of the competencies that trainees now need to acquire. Opportunities to acquire leadership skills will need to be sought out in the same way that clinical training is. Trainees can develop a structured learning plan based on the curriculum using formative assessments and reflection to evidence the leadership competencies they gain. Trainers can draw on the existing management infrastructure to provide trainees with leadership and management experience.

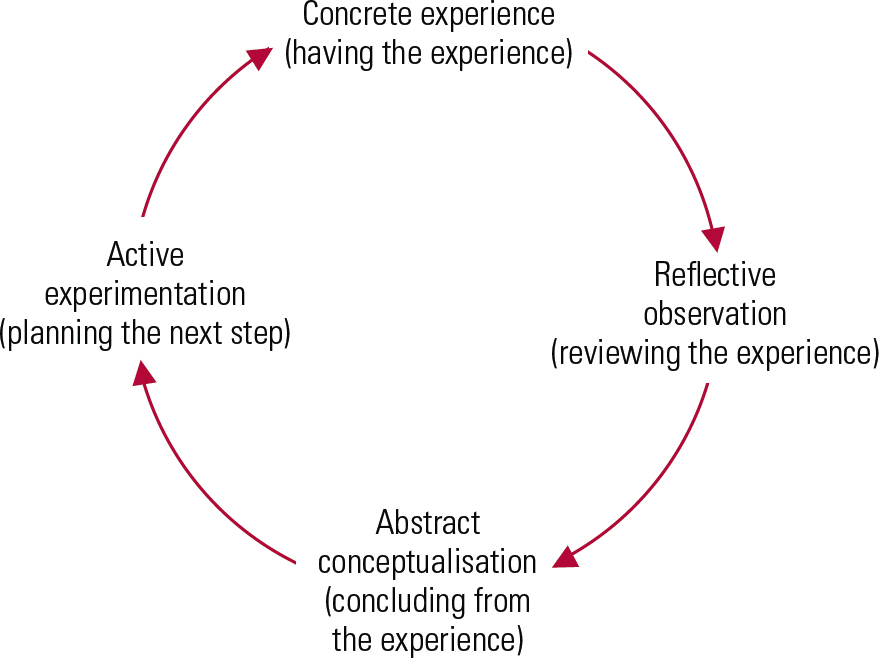

The principles of adult learning can be applied to gaining management competencies (Fig. 2). The learning process begins with the trainee carrying out a supervised project and then observing the effects. Next, the trainee needs to understand these effects in the particular context, so that they can recognise and anticipate how best to deal with similar situations in the future. The third step is for the trainee to understand the general principle underlying the particular training experience. The final step is to apply the new knowledge in new circumstances (generalisation) (Reference Kolb, Fry and CooperKolb 1975).

FIG 2 Adult learning (after Reference Kolb, Fry and CooperKolb 1975).

Educational supervision offers an ideal space for reflective observation and the development of abstract concepts. It is important for the trainee to be aware of their own learning style and to incorporate this in developing and achieving an effective personal development plan.

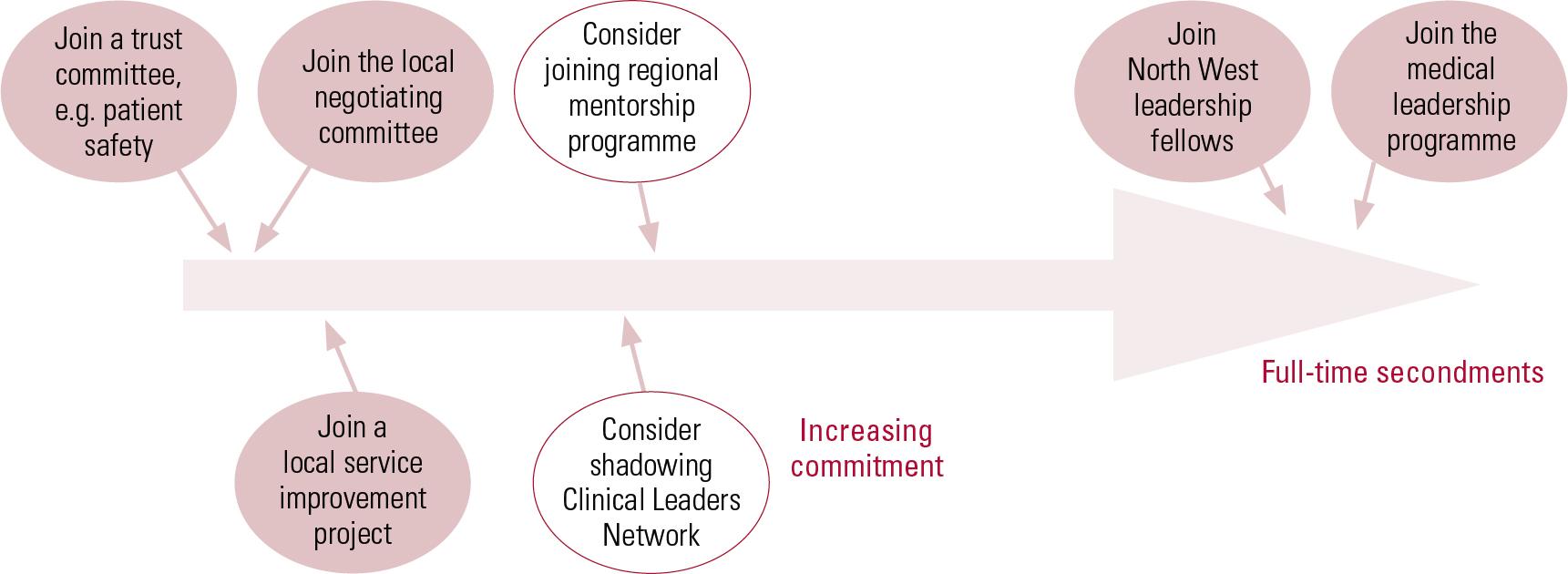

Organisations must respond to the changing training needs of junior doctors. A good example is the approach taken by the North West Strategic Health Authority (NHS North West) in England, which has taken the lead by involving junior doctors in leadership roles. As part of their regional strategy to encourage more junior doctors into leadership positions, they have developed a North West Clinical Leadership ‘pick-n-mix’ model (Fig. 3), providing opportunities for junior doctors to take part in several management and leadership activities (Reference Garg and Ahmed-LittleGarg 2009). Trainees can participate in and/or set up service improvement projects in their local organisations or sit on local committees. Those wishing to seek further opportunities can shadow senior clinical and managerial leaders or join their regional mentorship programme. Trainees wishing to pursue a leadership and management career path can apply for the NHS North West Deanery's Medical Leadership Programme or a full-time, year-long secondment as a leadership fellow. The programme offers junior doctors the opportunity to undertake management training alongside clinical training, spending 50% of their time engaged in leadership and management-related activities over a period of 4 years.

FIG 3 The North West clinical leadership ‘pick-n-mix’ model (after Reference Garg and Ahmed-LittleGarg 2009, with permission).

Trainees can gain leadership experience through the workplace at three levels: the corporate trust level, the directorate level and the individual level (Box 2).

BOX 2 Examples of ways to gain leadership experience in the workplace

At trust level

-

• Corporate induction

-

• Forum for trainees to communicate with management

-

• Involvement in trust-wide projects

-

• Attending trust board meetings

-

• Shadowing external stakeholders such as social services, commissioners

At directorate level

-

• Chairing team meetings

-

• Involvement in local service improvement projects

-

• Writing a business plan

-

• Attending clinical governance meetings

At individual level

-

• Representation on key committees such as local negotiating committees and serious incident review panels

-

• Developing a knowledge base by reading the Health Service journal and other documents produced for the NHS (such as A Guide to Finance for Hospital Doctors and A Junior Doctor's Guide to the NHS)

-

• Obtaining postgraduate qualifications in leadership and management

Leadership experience at corporate trust level

All NHS trusts and health boards need to establish training opportunities in an environment that is conducive to the development of effective leadership (Reference EdwardsEdwards 2007; Reference RoebuckRoebuck 2008). The junior doctors’ rotation allows trainees the opportunity to observe different practices in different services. Organisations offering these rotations can create an environment in which junior doctors feel encouraged to provide feedback and suggest new ideas to improve patient care. Within such an environment, junior doctors are likely to feel empowered to work alongside management as ‘agents of change’ from an early stage in their career.

A corporate induction provides an opportunity to outline the vision of the organisation and to create a sense of teamwork and institutional loyalty (Reference Stanton and LemerStanton 2010). Induction is an opportunity to learn about the structures and the function of the organisation and allows for engagement between the trust management and junior doctors. Organisations can provide opportunities for trainee representation on groups such as serious incident review panels, local negotiating committees and audit committees. A forum at which trainees can communicate with management can assist the organisation in understanding the challenges that junior doctors face (Box 3).

BOX 3 Involving junior doctors in trust management

A Midlands hospital employed a junior doctors liaison coordinator to improve communication between junior doctors and the trust management. The post holder was provided with office space in the doctors’ mess to ensure accessibility to all. Email lists of all junior doctors were set up to encourage their inclusion in electronic communications between trust staff, and a monthly newsletter was produced for the doctors’ mess. The trust also organised a monthly junior doctors’ forum and a lunchtime event where doctors could share their views or find out more about topics that concerned or interested them. As a result of this initiative, it was observed that junior doctors were more willing to take their ideas on service improvement to the trust management and the number of junior doctor representatives in the trust's steering groups increased.

This example demonstrates that when organisations create the ‘right’ environment, it is possible to engage with junior doctors and harness their energy as ‘active agents of change’.

Learning outcomes for the junior doctors involved

-

• Developing insight into the local healthcare organisation

-

• Understanding the role of managers in a healthcare organisation

-

• Seeking opportunities to participate in management projects at the organisational level

-

• Demonstrating an ability to be an active agent of change by undertaking service improvement projects

Junior doctors can seek opportunities to shadow the chief executive or the board of directors, which can help them understand the realities of day-to-day NHS management (Box 4). They can observe the challenges faced by managers, see how decisions are made at board level, develop a better understanding of the needs of the broader healthcare environment and appreciate how different parts of the service link up (the interface between mental health services, primary care, Social Services and the voluntary sector). Shadowing senior clinical and non-clinical leaders may be an opportunity to observe and learn different leadership styles and approaches. It may help break down some of the doctor–manager divide, paving the way for good working relationships in the future. Attending governance meetings can help junior doctors understand the seven pillars of clinical governance (Box 5) and where audit fits into the bigger picture. They can also seek opportunities to present their audit findings at these meetings. Participation in trust-wide projects as part of a steering group can provide opportunities for multidisciplinary working outside of the clinical context, understanding the principles of project management, engaging with stakeholders and benchmarking best practices.

BOX 4 The benefits of observing an NHS trust board meeting

Dr X, a specialty trainee, attended his first board meeting at the encouragement of his supervisor. During the meeting, the board looked at the lessons to be learnt from serious incident reviews and performance data, including clinical quality indicators and financial performance of the trust, and reviewed strategic plans for the future of the organisation. Dr X observed how the non-executive directors challenged the chief executive and his team. He also observed a consultant psychiatrist presenting a business case for a new service to the board for its approval. By observing the meeting, the trainee was able to learn more about the structure of the organisation and the role of regulatory bodies such as Monitor (the independent regulator of NHS foundation trusts), and appreciate the difference between executive and non-executive directors. He was able to write a reflective piece as evidence of his understanding of the structure and function of the board in an NHS trust.

Learning outcomes

-

• Understanding the structure and function of a board in the organisation

-

• Understanding the organisation's policy and practice at a local level

-

• Developing an understanding of different styles and approaches of leadership

BOX 5 The seven pillars of clinical governance in the NHS

-

1 Risk management

-

2 Clinical effectiveness

-

3 Education, training and continuing personal development

-

4 Use of information

-

5 Staffing and staff management

-

6 Clinical audit

-

7 Patient/service user and public involvement

Leadership experience at directorate level

At the directorate level, junior doctors can participate in a range of activities within their departments that can be facilitated and supervised by their educational supervisors and site tutors. It is important that trainees and their educational supervisors identify the relevant educational needs from the curriculum. At the start of their posting, they should draw up a personal development plan (PDP) with specific goals that are achievable within a realistic time frame and make sure that resources will be available. The principles of adult learning (Fig. 2) advocate that trainees make time for adequate reflection on these various projects. The newly developed assessment tool, direct observation of non-clinical skills (DONCS; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010a: p. 80), can be utilised to assess several different leadership/ management activities depending on the trainee's level of competence. Activities might include: chairing a journal club or case-based discussions; audit and teaching presentations; writing business plans; and coordinating ward rounds and outpatient lists. The junior doctor should also seek out non-clinical supervisors to participate in circumscribed projects within the directorate. Structured teaching on how to make the best use of reflective practice should be readily available and supported within the trust. As part of the trainee's mid-point and final educational reviews, the progress of projects and the development of these non-clinical skills should be reviewed and the PDP should be updated if necessary. In the future, workplace-based assessments (WPBAs) aimed specifically at leadership competencies might be developed.

Trainees are already involved with directorate-level management projects as part of their clinical work. Audit is a good example of an area in which several leadership competencies could be developed. The identification of a service need, the gathering and analysis of data, making recommendations and the presentation of findings to fellow clinicians allow the trainee to become more confident in taking the lead on a project. The trainee could work with the team or the directorate to implement the recommendations of their audit project. This would help them understand the practicalities of managing change: negotiating, designing and planning the process of change, communicating the need for change to stakeholders, engaging the team in the change process and reviewing the impact of change (Boxes 6 and 7).

BOX 6 An audit project on lithium levels

During his placement with an adult community mental health team, Dr X conducted an audit to look at monitoring of lithium levels. He found that many patients missed their regular blood tests for lithium levels but were still being issued prescriptions for the drug. At a team meeting, he presented his audit findings and recommendations for change. With the support of his educational supervisor, he got involved in designing and planning the process of change to implement the findings of his audit. His educational supervisor negotiated for him to have supervision for the project from the directorate manager. He worked alongside a managerial colleague in engaging with the general practitioners (GPs) to agree on a plan to jointly manage patients on lithium. He presented his audit findings, argued the need for change, and engaged with his team members and GP colleagues to implement the change. On re-auditing after 6 months, he was able to show an improvement in the regular monitoring of patients on lithium.

Learning outcomes

-

• Questioning existing practices to improve services

-

• Understanding the principles of management of change

-

• Demonstrating ability to work with managerial and GP colleagues

BOX 7 Writing a business proposal for funding

In her placement with a child and adolescent mental health team, Dr B took on a project to audit the pilot clinic for adolescents aged 16–18 with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Her consultant asked her to write a business proposal to apply for funding to continue providing the service. As part of the business plan, she met with the stakeholder GPs, commissioners and paediatricians to gather their views on the need for such a service. In addition, she looked at the number of young people over the age of 15 with a diagnosis of ADHD who would be potentially needing a service in the following few months. Under the consultant's supervision, Dr B arranged to meet with the finance director of the trust to calculate how much the service might cost. In addition, she looked at the various options for providing the service and their strengths and weaknesses. In this way, Dr B was able to provide succinct evidence to support funding of the new service.

Learning outcomes

-

• Understanding the principles of developing a business plan

-

• Demonstrating active involvement in service design and development

-

• Demonstrating ability to design and implement programmes for change, including service innovation

-

• Demonstrating a range of leadership skills, including planning, organising and example setting

Educational supervisors should encourage junior doctors to seek out opportunities at a site-specific level, for instance coordinating a rota, chairing/attending meetings or steering groups, preparing a draft tender/business plan and audit. Juniors could assist in writing team annual reports by collecting and analysing routine outcome data. Spending time with stakeholders such as Social Services and primary care commissioners can also help establish networks and foster an appreciation of how these support mental health services outside of the hospital. Trainee representation on patient complaints and serious case review panels can help junior doctors understand how to manage risk and handle complaints. This should be supported by structured supervision, which should emphasise confidentiality and the tensions between corporate and clinical priorities.

Junior doctors should try to gain a better financial understanding of how the NHS is run. At a directorate level they could, under supervision, get involved in writing a business plan for the service. This can be a valuable opportunity to understand the basics of business management principles such as priority setting, gathering evidence to support the need for change and understanding the financial implications of the service changes.

Leadership experience at the individual level

At the start of their posting, trainees should identify the gaps in their knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviour, and work out a coherent and achievable PDP. The Medical Leadership Competency Framework (Fig. 1) and the College curriculum can be used to structure this leadership PDP. Another useful resource is LeAD, an interactive e-learning website developed by the NHS Institute of Innovation and Improvement and the AoMRC to help doctors understand their role in managing and leading the health service (www.e-lfh.org.uk/projects/lead/index.html). LeAD may be used to help develop a PDP and also to acquire a knowledge base regarding leadership and management theories. Trainees should be encouraged to develop an inquisitive mindset about healthcare policy at a national and local level. Publications such as the Health Service Journal (www.hsj.co.uk) will bring the trainees up to date on topical health policy debates in the UK. The Department of Health has published a number of useful documents, such as A Junior Doctor's Guide to the NHS, which explains the structure and functions of the NHS and its ancillary bodies in a simple manner (Reference McCay and JonasMcCay 2009). The AoMRC and the Audit Commission have produced A Guide to Finance for Hospital Doctors (Academy of Medical Royal Colleges 2009), which explains in lay terms what a budget is, how to read a budget report, how money flows around the NHS, payment by results and primary care trust commissioning, among other things. Reading this can improve trainees’ knowledge base and give evidence of some of the competencies outlined in the curriculum relating to understanding principles of managing available financial resources and understanding budgets.

There is a growing body of literature looking at evidence-based management (Reference Walshe and SmithWalshe 2006). For trainees wishing to enhance their theoretical understanding of leadership and management, a number of postgraduate courses are available throughout the country. Postgraduate deaneries often run courses on time management and developing skills for conflict resolution and negotiation.

It is imperative that trainees gain hands-on practical leadership experience beyond theory. Getting involved in a management project can help trainees demonstrate their competencies for their portfolios. Chairing meetings can be used as a platform to demonstrate skills in presenting, listening, coordinating, delegating and negotiating. This can be observed by a supervisor, who can provide feedback on the trainee's performance. Trainees can enhance their learning by writing a reflective piece on their experience. Representing colleagues on different committees, such as the Junior Doctors Committee of the British Medical Association, local negotiating committees and the College's Psychiatric Trainees’ Committee, can help develop skills in negotiating, communicating and networking with managerial leaders at both local trust and national level.

Developing the personal qualities of a leader is even more important than building a sound knowledge base. Feedback from colleagues can give trainees insight into their personal communication skills, interpersonal skills and professionalism. Trainees can reflect on their own leadership styles by using Myers–Briggs style personality indicators, the Belbin Team Inventory and the Transformational Leadership Questionnaire (these and similar tools can be found on the internet). Such tools can aid the process of self-awareness, thus helping trainees to recognise their strengths and weaknesses and change their behaviour accordingly. Myers–Briggs style personality indicators, for example, help individuals to understand their personality type, how they perceive the world and make decisions, and appreciate differences between people. This can aid the development of interpersonal skills and enhance team working by helping the trainee understand how their prejudices and differences affect their behaviour. Critical self-assessment by reflecting on the results of these inventories and drawing up an action plan to work on areas of weakness is very important. This, together with multisource feedback, can be used to demonstrate how the trainee is developing the personal qualities needed by a leader.

The role of educational supervision, mentoring and coaching

All trainees are required to have educational supervision throughout their training period (Department of Health 2007). Educational supervisors should ensure that trainees provide safe and appropriate patient care and give them guidance and feedback on their personal, professional and educational development (Reference Kilminster, Cottrell and GrantKilminster 2007).

Effective supervision of leadership or management projects should include identifying a list of potential local resources, including courses, shadowing opportunities and project work (including audit), and fitting these to the individual trainee's needs within a personal project plan. The supervisor should ensure that projects are achievable, with measurable time lines and points of assessment. Educational supervision of leadership projects should enable the trainee to develop greater autonomy and increasing responsibility, depending on their abilities and level of training.

Mentoring and coaching can both be viewed as specific examples of supervision, in the sense that they all involve similar interpersonal skills. Aspects of mentoring and coaching are clearly part of the educational supervisor's role (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008). However, there are important differences between the two (Table 1). In developing their leadership skills, trainees might want to seek out mentoring and coaching from different individuals, depending on their specific career direction.

TabLE 1 Differences between mentoring and coaching

| Mentoring | Coaching | |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Information/personal growth | Goals/outcomes |

| Agenda | Set by trainee | Outcomes |

| Disclosure | Mentor offers wisdom/resources | Assist trainee in identifying need |

| Relationship | Mutually selected | Comes with the job |

| Arena | Whole career | Task related |

| Time | Indefinite | Time-limited to achieving outcome |

Mentoring

Mentoring refers to guidance and support offered by a more experienced colleague, usually within the same profession. Mentoring is most effective when it occurs outside formal training structures. The mentor should therefore not be the current educational supervisor and the relationship is therefore necessarily different. Meaningful mentoring by clinical and non-clinical leaders can enable individuals to think more widely about their work, offer a space to reflect on their learning, increase self-awareness and help personal development. Mentoring can also enhance confidence and feelings of control and reduce stress (Reference Sackin, Barnett and EastaughSackin 1997; Reference Steven, Oxley and FlemingSteven 2008). Trainees can also help each other, meeting to offer mutual support, perhaps in action learning sets.

Coaching

Coaching could be seen as the more active part of structured supervision, aimed at unlocking the individual's potential to maximise their performance (Reference WhitmoreWhitmore 1996). It requires working towards set goals and objectives. A coaching relationship can help the trainee to define their goals, identify obstacles and self-imposed limitations standing in their way, and motivate them into action towards achieving results (Reference BiroBiro 2010). To be a successful coach requires knowledge and understanding of coaching process as well as the variety of styles, skills and techniques that are appropriate to the context in which the coaching takes place. However, it does not require the coach to be of the same profession as the trainee (Reference ParsloeParsloe 1999). Coaching is concerned with performance. Workplace-based assessments would lend themselves to performance evaluation and enable a starting point for effective coaching.

Conclusions

Leadership is an integral component of the work of all doctors. The challenge of negotiating clinical and management responsibilities is daunting, but one the medical profession needs to face squarely to ensure that their legitimate input is felt within the NHS. Medical training should equip the doctors of tomorrow with the opportunity to develop leadership skills, but this must not be done at the expense of their clinical training. At the start of each posting, it is therefore imperative that educational supervisors carefully plan with their junior doctors what opportunities exist, and how much time and effort should be devoted to them. Educational supervisors should also familiarise themselves with the Medical Leadership Competency Framework (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010), which will enhance their supervisory role. There may be opportunities to seek supervision from non-clinical leaders, especially when the trainee is engaged in a service improvement project, but this may need to be commissioned or paid for.

In this article we have attempted to demonstrate through case examples that many management experiences can be sought to address the demands of competency-based curricula in the trainee's workplace. Trainees’ ultimate success in developing these skills and values depends as much on how they are supported by their educational supervisors and on the culture of the host organisation as it does on their own efforts and abilities. It is essential that educational supervisors are as fully acquainted with the leadership/management component of the curriculum as they are with its direct clinical components and that they encourage trainees to take up these important learning opportunities.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Medical leadership is seen as key by:

-

a the General Medical Council

-

b the Postgraduate Medical and Training Board

-

c the Department of Health

-

d all of the above

-

e none of the above.

-

-

2 In specialty training, many doctors do not access appropriate leadership training until:

-

a the final 6 months of higher training

-

b the final year of core training

-

c the start of core training

-

d the start of higher training

-

e they are qualified consultants.

-

-

3 Which of the following does not fit within the personal qualities as set out in the Medical Leadership Competency Framework?

-

a developing self-awareness

-

b managing others

-

c continuing professional development

-

d acting with integrity

-

e maintaining relationships.

-

-

4 As regards supervision and mentoring:

-

a supervision is the same as mentoring

-

b supervision should not be provided by a non-clinical leader

-

c supervision is looking at the ‘bigger picture’

-

d mentoring can enhance confidence and has been shown to reduce stress

-

e mentoring can only be provided by a non-clinical leader.

-

-

5 Junior doctors’ understanding of management issues within the NHS could be enhanced by:

-

a A Guide to Finance for Hospital Doctors

-

b A Junior Doctor's Guide to the NHS

-

c Health Service Journal

-

d all of the above

-

e none of the above.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | a | 3 | b | 4 | d | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.