Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has been described as part of the third wave of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) (Reference Hayes, Hayes, Follette and LinehanHayes 2004a). The first wave was traditional behavioural therapy, which focuses on observable behaviour and direct interaction with the environment. Pavlov, Watson, Thorndike and Skinner are among the well-known figures from that era. Exposure work and skills training are the main interventions within a clearly defined empirical framework.

Such interventions worked but were unable to account for the problems of thinking and the influence of private events on behaviour. In response to this weakness, cognitive theories began to emerge and over the past 30 years cognitive methods have taken centre stage. In this second wave, Beck and Ellis have been the key figures, and illogical thinking or thinking error is seen as the primary cause of any problem. The evidence base for standard CBT is extensive, with an emphasis on outcome research in randomised control trials across a wide range of disorders.

The second wave was a tremendous advance but the scientific link between the processes of cognitive change and outcomes has not been established. This set the scene for the emergence of new treatment models that focus on the function of problematic cognitions rather than the content. The third wave differs from the first wave in that it has a considerable focus on private events, and it differs from the second in that it does not try to change the form or frequency of these private events. Over the past 15 years, these new treatments have developed an expanding evidence base. Based on acceptance and mindfulness procedures, this third wave of CBT includes dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT)Footnote † and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) as well as ACT.

Relational frame theory

Relational frame theory (RFT) has been developed over the past 25 years as a post-Skinnerian model providing an empirically based account of language and cognition (Reference Hayes, Barnes-Holmes and RocheHayes 2001) that underpins ACT. This theory emerges from earlier work on rule governance and derived stimulus relations in the behaviour analytic tradition. Relational frame theory extends these ideas to regard thinking itself as a special form of learned behaviour in its own particular class.

From the RFT perspective, language is seen as the main difference between humans and non-humans and relational framing as the core process in developing language. In a developmental continuum, more complex language abilities develop over time, and relational frames continue to expand throughout the lifespan.

Transformation of functions

Try the following exercise. Imagine that there is a screw stuck in the wall and you want to remove it. The only tool that you have is a toothbrush. With just this tool, a reasonable solution may not easily present itself. However, if we add another tool, a cigarette lighter, then a solution may be more apparent.

Relational frame theory attempts to offer an explanation of how human beings can solve problems like this in the absence of actual objects. The theory is interested in the process of thinking – how is it possible to imagine that the lighter could melt the plastic so that the toothbrush can be formed into a lever?

Another exercise: Ning4 is Cantonese for lemon. If you tried to imagine a Ning4 in front of you, what colour would it be and what would it look like? What would it smell like? What would it taste like if you took a bite?

In this example, knowledge of lemons is assumed. The human mind will then automatically make the relation between the lemon and the Ning4, and some or all of the properties of the lemon will transfer to the Ning4 – yellow, citrus, bitter. From an RFT perspective, it is the process by which the properties of the lemon are transferred to the Ning4 that is of particular interest.

This language ability is called ‘transformation of functions’ and it appears to have played a significant role in allowing the human race to become successful problem solvers and attain a position of dominance on the planet. However, there is a darker side to the process that can underpin many mental health disorders (Box 1).

BOX 1 Pathological transformation of functions

Imagine that when an accident took place, Bob Dylan was playing on the radio. It might then happen later that the same person was enjoying a meal out in an Italian restaurant when Bob Dylan was played as background music and they felt anxious as if for no reason. Over time, the anxiety provoked by the Dylan music could be transformed into the context of restaurants in general (irrespective of music) or Italian food. Perhaps buying a pizza in a supermarket could provoke anxiety, and then supermarkets and shops could elicit fear. It is easy to see how anxiety could become irrational quite quickly through transformation of functions.

From a clinical perspective, RFT shows how humans are able to interact with events purely on the basis of verbally ascribed functions, while being completely unaware of the underlying process of language. In the world of thought, the event and the person thinking about the event are usually experienced as one, so it appears real. Words alone can elicit pain. Consequently, in ACT clinical work, undermining the functions contained in language plays a central role, as opposed to changing the content of thoughts themselves.

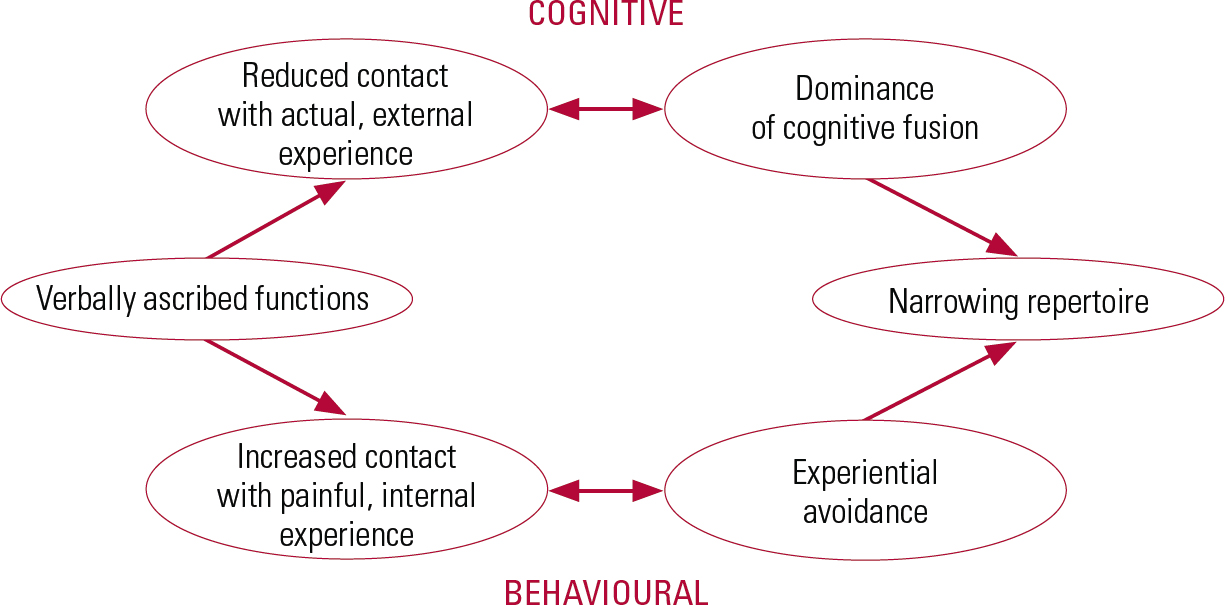

FIG 1 The process of formation of mental disorders.

The ACT model of psychopathology

Figure 1 shows the cognitive and behavioural processes that underlie many forms of psycho-pathology: cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance.

Cognitive fusion

The tendency to act in the world on the basis of verbally ascribed functions is referred to as cognitive fusion. The thought and the person thinking the thought become as one, or fused, hiding the nature of the language process. Fusion can lead to a loss of contact with actual events, or real experience, so that thoughts start to become self-confirming (Box 2).

BOX 2 An example of cognitive fusion

If someone with depression is fused with the thought ‘I don’t have enough confidence’, it is likely that they will do less. Doing less sets up a cycle in which there is a reduced contact with actual events and a further (natural) loss of confidence. Fusion with the thought is strengthened and a pattern is established that could develop into a mental disorder over time.

Experiential avoidance

From an ACT point of view, the increasing dominance of cognitive fusion is one aspect of the way in which psychopathology develops and produces a restricted repertoire. The other is more behavioural and emanates from the process by which verbally ascribed functions easily lead to negative emotions. For instance, worry can develop when thinking about the imagined future, and sadness or guilt can result from remembering the past. Mainly these are normal experiences and most people develop strategies to cope.

The situation becomes problematic when individuals try to suppress or avoid the pain that is evoked through thinking. This tendency is known as experiential avoidance, and has been defined as ‘the attempt to escape or avoid the form, frequency or situational sensitivity of private events, even when the attempt to do so causes psychological harm’ (Reference Hayes, Wilson and GiffordHayes 1996).

The same paradox tends to emerge in most mental health disorders: trying to get rid of unwanted private events leads to increased domination by those events. The behavioural impact is an increasingly restricted repertoire which, over time, develops into a mental health disorder (Box 3).

BOX 3 How experiential avoidance can lead to mental health problems

Social anxiety

Thinking of a forthcoming social event may evoke concerns about possible rejection or inability to make conversation. Choosing to avoid the event produces immediate relief but can lead to longer-term problems with social situations.

Psychosis

Hallucinations are an extreme form of verbal event. A person experiencing them may try many strategies, such as arguing them away, denying their occurrence or avoiding situations in which they might occur. Over time, this could cause hallucinations to dominate further and behaviour to become more extreme.

Therapeutic aims

Cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance tend to create behavioural repertoires that are insensitive to the events of the moment and inflexible in changing circumstances. The fundamental objectives of ACT are to undermine these processes and to help clients move forward in valued directions by developing behaviour that is sensitive to the current context (Box 4). Collectively, this is known as psychological flexibility, and an increased ability to adapt is the main aim of ACT.

BOX 4 Setting valued directions

A valued direction for many might be to improve health and fitness. In this context, going for exercise after work could be seen as workable (see text), whereas going home and sitting in front of the TV all night might be seen as unworkable.

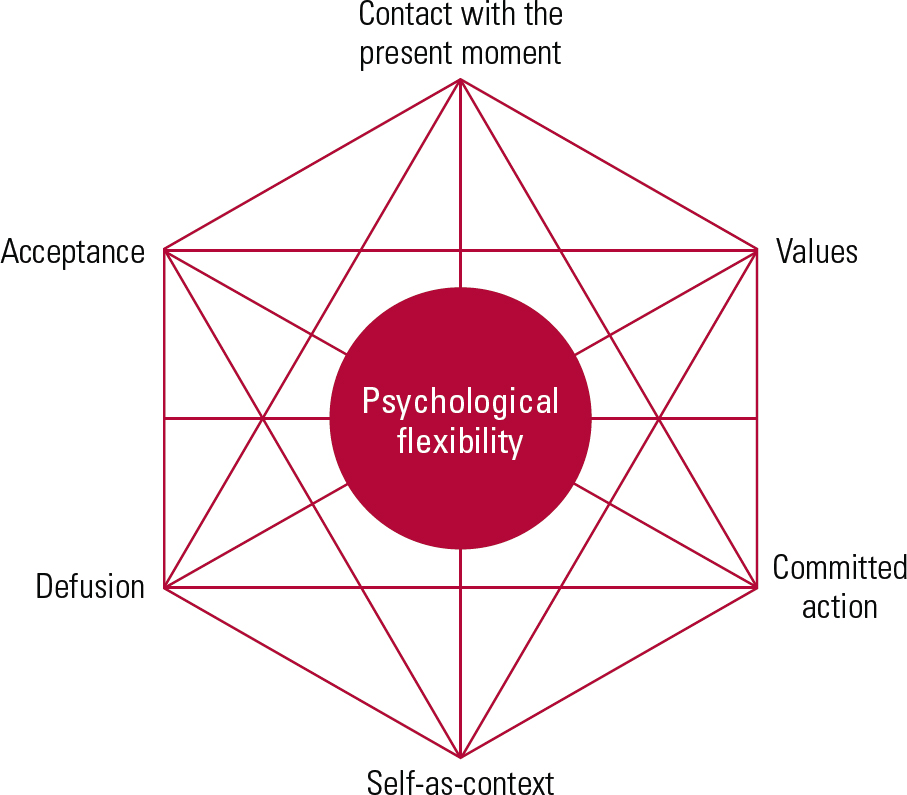

Therapy model

In their first presentation of ACT, Hayes et al defined six core components: acceptance; defusion; contact with the present moment; self-as-context; values (valued directions or actions); and committed action (Reference Hayes, Strosahl and WilsonHayes 1999). These are not sequential, but are interlinked to create a fluid model in which therapist flexibility is also important (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 The acceptance and commitment therapy model.

Acceptance

This means taking a position of non-judgemental awareness towards thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations as they arise. The process begins with the client learning to notice behaviours that are not moving towards values, known in ACT as unworkable. After that, the client moves on to noticing how attempts to control unwanted private experience leads to a struggle. Acceptance involves letting go of this struggle, while still working on external issues that can be changed.

Defusion

Cognitive defusion addresses the problem of cognitive fusion described above. It is about trying to dilute the impact of harmful functions contained in language. It involves trying to shift focus from the content of thoughts to the process of thinking itself, thus weakening the verbally ascribed functions. Defusion creates distance from the thoughts, as if the individual were standing back from their mind, like an observer.

Contact with the present moment

Clients are taught to notice their external and internal experience in the present moment. The practice of mindfulnessFootnote ‡ provides the foundation. Later, this can be extended into operant exposure routines in which clients learn to develop new behaviour, based on values that they choose (see below), in the presence of previously avoided experience.

Self-as-context

Cognitive fusion with thoughts such as ‘I’m worthless’ is referred to as self-as-content: the person’s identity is caught up in the content of the particular thought. Acceptance and commitment therapy assumes that, in order to fully experience painful feelings or really stand back from difficult thoughts without trying to change them, a wider perspective is necessary. This transcendent sense of self is referred to as self-as-context, and can be developed through defusion and mindfulness. From this perspective, the ‘observer’ self is not threatened by the content of experience, but is instead the context in which all experience unfolds.

Values

Clients are encouraged to clarify their valued directions or actions. These ‘values’ are neither feelings nor goals, but connect to a deeper sense of purpose and meaning as an ongoing process of behaviour. This component closely resembles modern existential ideas (Reference FranklFrankl 2006), where choice and freedom of action are the main focus. Consequently, in ACT the individual focuses on the future, as opposed to exploring the past, and their chosen values underpin all aspects of therapy.

Committed action

Committed action is about learning to move in valued directions while in the presence of unwanted or painful thoughts and feelings. The choice between an easy life and a rich, full life is presented, and clients are encouraged to find the willingness to have painful thoughts and feelings in the service of moving in a valued direction. Vitality develops as the client’s behaviour becomes more oriented to their underlying values.

Clinical style

Above all, the ACT therapist is aware of the traps in ‘literal’ language and will try to sidestep these through the use of metaphor, paradox and experiential exercises.

Metaphors have many advantages, being much more like pictures than the usual form of language. Well-chosen metaphors allow directly experienced contingencies to be more easily examined. Metaphors are often easier to remember and to transfer between situations, which helps in developing broader patterns of behavioural change.

Paradox is of particular importance to ACT because it plays such a significant role in breaking down language processes. It can help by highlighting the contradictions of language itself, for instance in instructions such as ‘try to be spontaneous’ or ‘just relax’. The ACT view of psychopathology is itself inherently paradoxical – the harder you try, the worse it gets – and the use of Zen-like stories (koans such as ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping?’) typifies the approach of the ACT therapist.

Experiential exercises conducted in the therapy setting allow clients to contact thoughts and experiences that are usually feared or avoided. The safer context can allow private events to be observed with more distance and detachment, allowing for behaviour to emerge that is more in line with values. Language processes can be seen, studied and more easily defused in this format.

Metaphorically, the therapist style in ACT is more like helping someone learn to swim than teaching them maths. The therapist may be seen more as a coach, trying to help the client get a feel for what is happening rather than explaining how it works.

Overview of interventions

The interventions of ACT are fully detailed in publications on the practical applications of the therapy (Reference Hayes and StrosahlHayes 2004b) and on therapist training (Reference Luoma, Hayes and WalserLuoma 2007). In addition, there are specific manuals for different diagnoses (Box 5). The strategies, metaphors and exercises below are summarised from the original reference book on ACT (Reference Hayes, Strosahl and WilsonHayes 1999).

BOX 5 Further resources

The main body of resources for ACT can be found online at the website of the US Association for Contextual Behavioral Science (http://contextualpsychology.org). The site includes information on:

-

• reference books

-

• self-help books

-

• published research

-

• DVDs

-

• training workshops

In addition, there is a great deal of material that can be downloaded:

-

• resources for clinicians

-

• discussions

-

• treatment protocols

(access to some resources require ACBS membership).

In the UK, the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) has an ACT special interest group (actsig@babcp.com).

Acceptance

The therapist identifies examples of unworkable behaviour (behaviour that is not moving towards the individual’s values) and develops suitable metaphors for them (Box 6). Once a suitable metaphor is found, the therapist refers to it each time the client mentions an unworkable behaviour. In this phase the therapist sets homework and conducts exercises that amplify the cost of unworkable solutions from the perspective of valued living.

BOX 6 The tug-of-war metaphor

Imagine that you are standing on one side of a deep ravine. Between you and the other side is a chasm with a long drop to a certain death on the rocks below. You are in a tug of war with a monster that you cannot see, on the other side of the ravine. Each time you pull, you make one step back, but in response the monster pulls even harder and you take two steps forward towards the ravine. Slowly you are inching closer to the edge, feeling increasingly anxious.

(Adapted from Reference Hayes, Strosahl and WilsonHayes 1999)

Once the client has started to notice the futility of the struggle to control unwanted feelings or thoughts, the therapist will introduce the idea that all of these are forms of ‘control’ that operate paradoxically – ‘The harder you try, the worse it gets’. The idea of letting go is allowed to surface, and experiential exercises are used to undermine avoidance further and dichotomise the choice between control and willingness.

Defusion

The mind is introduced as a functional organ that just does a job. In response to an example of the client’s cognitive fusion, the therapist may well ask ‘Is that what your mind is telling you?’ or say ‘Thank your mind for that thought’.

‘Leaves on the stream’ (Box 7) is one of several mindfulness exercises that can be used to help the client develop an experiential sense of distance from their mind/thoughts.

BOX 7 Leaves on the stream: a mindfulness exercise

In this exercise, the client is first brought to a mindful state and then, with eyes closed (if the client agrees), invited to imagine sitting beside a stream that has large leaves floating down it. As the client sits there, they are invited to notice their thoughts. The therapist suggests that, as each thought occurs, the client place it out on a leaf and watch as the stream takes it along. The idea is to experience, to feel, the difference between the thought in the mind and the thought on a leaf.

(Adapted from Reference Hayes, Strosahl and WilsonHayes 1999)

Examples of more structured defusion exercises include inviting the client to write thoughts on cards and to sing them out loud, or say them very slowly or in a silly voice. Imaginal work can be done to find voices or characters that render the thought less believable, or more comical.

Such exercises are used to increase interaction with the fused thought in a new context.

Contact with the present moment

The therapist is alert for experiential avoidance during sessions and gently brings the client back into contact using questions that reorient attention. It is common to hear interventions such as ‘What are you noticing right now?’ or ‘What are you aware of in this moment?’ throughout all phases of therapy.

Formal mindfulness practices can be used to help the client develop this ability. These exercises combine with operant exposure as the therapist tries to amplify experiencing and develop new behaviours in the presence of previously avoided experience.

Self-as-context

In the chessboard metaphor, the client is encouraged to recognise the distinction between the chess pieces and the chess board. Thoughts and feelings are the chess pieces, which are constantly moving, opposing each other in a never-ending struggle. The client is encouraged to adopt the metaphorical role of the board, which just holds the pieces.

Therapists ask clients to notice experience on a regular basis in sessions. The self-as-context question is then to ask ‘Who is noticing that?’. In this component, longer exercises are used to help the client find experiential contact with the ‘observing self’.

Values

The client’s values (valued directions or actions) are thought of metaphorically as directions on a compass. The individual is taught to distinguish values from feelings and directions from goals. Ogden Lindsley’s ‘dead man’s test’ can be used effectively to counteract the normal tendency to think in terms of symptom removal: if a dead person can achieve something, then it is not usually considered a good direction for a living person. For instance, dead people aren’t depressed, don’t have anxiety or OCD and don’t take drugs. This is an effective device to focus back on the behavioural nature of values as living action.

Homework and assignments are used in this phase to clarify values and identify any discrepancy between how important a compass point is and the amount of actual movement towards it. Imaginal work is used to establish even greater contact with values and to strengthen motivation.

Committed action

Helping clients break tasks down into small steps is very similar to standard practice in behavioural therapy. If the client is struggling with feelings or is fused, the passengers-on-the-bus metaphor (Box 8) can be used as a way of examining the relationship with unwanted content or of creating a sense of distance. The therapist may even turn the metaphor into an experiential exercise using props or index cards. Various experiential exercises will be used to build new patterns of action using small steps. Throughout, the emphasis is on generating new behaviour towards values while in the presence of previously avoided feelings. The ‘pick up your keys’ exercise (Box 9) illustrates this approach and shows how willingness is worked on. Such new behaviour is the overall goal of ACT.

BOX 8 Passengers on the bus

Imagine that your life is a bus. On the front of the bus is the route, which is your value. As you try to drive the bus in a valued direction, passengers jump on board and start to give you a hard time. These are the thoughts and feelings that you struggle with. The passengers can become very threatening and so you start to argue with them, or placate them or even try to get them off the bus. What happens to the bus when its driver is struggling with the passengers?

(Adapted from Reference Hayes, Strosahl and WilsonHayes 1999)

BOX 9 Pick up your keys

For the purposes of this example, let’s say that the client is struggling with anxiety. The therapist would ask the client to get out their keys and hold them. The therapist would then ask the client to nominate one of the keys to represent anxiety. Once selected, the therapist would explore the valued direction involved. Once that has been established, the therapist would encourage the client to pick up this key and hold it while moving in that direction. Imaginal exposure work can often be conducted during sessions and the exercise can be generalised quite easily as most people take their keys out with them.

Example of the therapy protocol

Acceptance and commitment therapy has been used successfully as a four-session intervention for psychosis in an in-patient setting (Reference Bach and HayesBach 2002; Reference Gaudiano and HerbertGaudiano 2006), showing an approximate 50% reduction in the readmission rate at 3 months compared with treatment as usual. Below we illustrate ACT in such a setting. The sessions are one to one and each lasts 1 hour.

Session 1

-

• The therapist explores the unworkable strategies the client has been using, and suggests that these solutions may actually be part of the problem.

-

• The nature of hallucinations is discussed and put on a ‘thoughts continuum’ with other difficult content, such as paranoid or self-harming thoughts.

-

• The therapist points out that the difference between hallucinations and normal content is not actually that wide, but it is how content is responded to that differs greatly and distinguishes between who is in hospital and who is not.

-

• Believability of hallucinations is introduced and defusion explained through the metaphor of a computer screen, where thoughts can be treated as no more than just words on a screen.

-

• The idea of noticing hallucinations instead of believing them is further developed through the leaves-on-the-stream exercise (Box 7).

-

• Finally, the strategy of doing what works is presented, linked to treatment adherence and the client’s values.

Session 2

This is held 3 days after the first session.

-

• Clients are asked to describe their symptoms in detail, including content, frequency and severity of distress.

-

• A detailed discussion is held to see how the client responds to thought content, and especially to establish whether their main strategy is to get rid of the unwanted symptoms.

-

• The responses are examined to establish whether it is this strategy that actually led to hospital admission. Other negative consequences are considered, such as legal, housing and relationship difficulties.

-

• The futility of the struggle is amplified, and the alternative of letting go is brought in through the tug-of-war metaphor (Box 6).

-

• Letting go of the rope is linked with acceptance and described as an action with the choice between doing what you want and doing what works.

-

• These two polarised options are then put into the context of hospital admissions, and acceptance of treatment is linked to improved choice in valued living.

Session 3

The third session is held 3–5 days later and focuses on developing acceptance.

-

• The distinction between the process of having an hallucination and being fused with the content of that hallucination is learnt by practising defusion statements such as ‘I am having the thought that the Prime Minister is Satan’, contrasted with saying ‘The Prime Minister is Satan’.

-

• The client is asked to think about the consequences of acceptance compared with past attempts to change content.

-

• Valued directions are explored again, and the client is asked to compare the consequences of trying to control symptoms v. acceptance in relation to these values.

-

• A detailed discussion follows, comparing whether it is better to believe the content of thoughts or to choose valued directions, looking at what is workable.

-

• Workability is then brought into the context of hospital admissions and the client is helped to generate new, alternative strategies that will work for them.

Session 4

This is held within 3 days of the client’s discharge from hospital. This is mainly a review of the previous sessions.

Research

Since the publication of the first ACT reference book (Reference Hayes, Strosahl and WilsonHayes 1999), evidence on the efficacy of the intervention has been accumulating at an increasing rate and for a widening range of conditions. There are currently over 50 published randomised controlled trials (RCTs). During recent years there have been three independent reviews of these data (Reference ÖstÖst 2008; Reference PullPull 2008; Reference Powers, Zum Vorde Sive Vording and EmmelkampPowers 2009) comparing ACT with standard CBT.

The reviews of the RCT outcome data contain areas of agreement and of difference. The reviewers all point to methodological flaws in the ACT studies, and the ACT community is in agreement with this. There is also general agreement that the ACT data show promising outcomes that are in line with CBT outcomes but no better. A reply from the ACT perspective (Reference GaudianoGaudiano 2010) points out differences in the life cycle of the two therapies: standard CBT has been generating RCTs for over 35 years, so trials are now more focused on controlling the methodology, whereas research into ACT is only around 10 years old and is still focusing more on outcomes and conditions. Gaudiano also notes ACT studies have focused more on complex conditions and less on the standard mood disorders such as depression and anxiety that are the focus of much of the CBT literature. The two therapies do not differ much in effectiveness in mood disorders, but show different processes of change. Acceptance and commitment therapy shows promise in treating conditions that have not responded well to CBT. The debate will continue.

In possibly the most balanced review of the ACT outcome data, Reference PullPull (2008) offers this summary:

‘The available evidence suggests that ACT works through different processes than active treatment comparisons, including traditional CBT. Although currently available data are promising there is, however, a need for more well controlled studies to verify whether ACT is generally as or more effective than other active treatments across the range of problems examined.’

Beyond outcome data, the ACT community is working to identify mediational effects of the six components of the model. The 7-item Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II (AAQ-II) (Reference Bond, Hayes and BaerBond 2011) uses the construct of ‘psychological flexibility’ to summarise the effects of the six components, with experiential avoidance at the lower end of the scale.

In the future it is hoped that mediational effects will be established for each of the six components. The start of this seems to be happening with the acceptance component in the area of chronic pain (Reference Mason, Mathias and SkevingtonMason 2008), with acceptance correlated to the World Health Organization quality of life measure.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Within ACT, values can best be described as:

-

a beliefs about what is right

-

b important behavioural directions

-

c goals that have a high priority

-

d achieving good feelings

-

e a moral code.

-

-

2 Psychopathology in ACT can be understood as:

-

a the result of past experience

-

b faulty thinking

-

c lack of skills

-

d experiential avoidance

-

e inadequate values.

-

-

3 Which one of the following is an example of defusion?

-

a ‘I can’t go out and visit my friends’

-

b ‘People should always tell the truth’

-

c ‘I’m having the thought that this is bad’

-

d ‘I get things wrong most of the time’

-

e ‘Nothing ever works out for me’.

-

-

4 Which of these is not one of the six core components of ACT?

-

a committed action

-

b self-as-content

-

c contact with the present moment

-

d acceptance

-

e values.

-

-

5 Which of the following would you most associate with the acceptance component?

-

a the chessboard metaphor

-

b mindfulness practice

-

c dead man’s test

-

d the leaves-on-the-stream exercise

-

e the tug-of-war metaphor.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | b | 2 | d | 3 | c | 4 | b | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.